PISA has now been going since 2000, with England participating in every cycle. Yet involvement in PISA does not come cheap. It costs more than £2m every three years for England, Wales and Northern Ireland to take part. Not to mention the burden it places upon nearly 500 schools.

It therefore seems important that we consider whether all this time and effort is worthwhile. Is England really getting enough out of its continued participation in the PISA study?

This blogpost focuses on four key reasons why England has participated in the PISA study, and the value that they bring.

1. PISA enables comparisons to other countries

One of the most exciting things about PISA when it started was that it enabled comparisons of educational achievement with other countries. Yet, with 2018 being the seventh of the tri-annual cycles, this motivation for participating in PISA has gone a bit stale. Nothing has really changed, has it?

East Asia, along with Finland and Estonia, leads the world, while it is mainly lower- and middle-income countries that are found towards the bottom of the rankings. England then jockeys for position somewhere in the middle, with most other developed European nations.

Yet there continue to be two areas where such cross-national comparisons continue to be interesting and important. First, with education a devolved power, PISA remains the premier resource to measure the divergence of education systems and achievement across the four constituent countries of the UK.

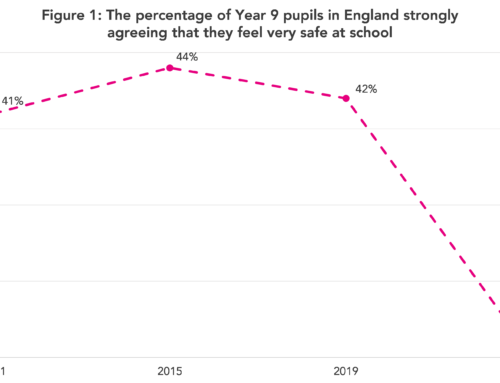

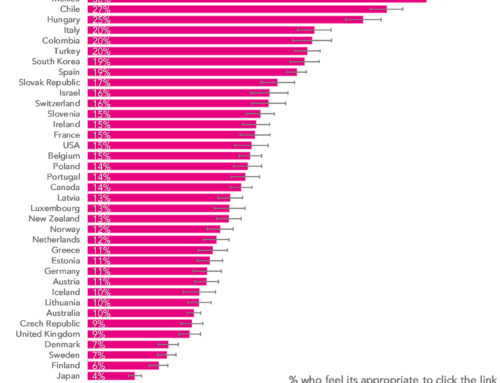

Second, as previous blogposts in this series have shown, PISA provides a means to benchmark England’s position in the world in a whole host of areas other than educational achievement – whether this be social media use and addiction to the internet or even the amount that teenagers are prone to exaggerate.

When considering whether England should continue to participate in PISA, the value of these more contextual comparisons should not be overlooked.

2. PISA provides an independent measure of trends in educational achievement

It is little secret that England previously suffered a problem with grade inflation, with GCSE grades increasing year-upon-year. Hence a key use of PISA previously has been to provide an independent measure of education standards in England over time.

This, in my view, was always one of the key reasons why continued participation in PISA was important. Yet there are two reasons why I no longer believe this holds true.

First, England’s exam regulator Ofqual now conducts the national reference test which essentially serves this purpose. And, in many ways, it does this better than PISA (larger sample sizes, conducted annually rather than tri-annually, more common questions between administrations).

Second, I have previously raised concerns about the comparability of PISA data over time [PDF], particularly with the wide range of methodological changes made in PISA 2015 and 2018, including the shift to computer-based assessment.

It therefore seems hard to argue for England to continue to participate in PISA for this purpose.

3. PISA can influence education research, policy and practice

Why do we collect education data? Ultimately, it is with the hope that it will provide new insights that will influence education policy and practice, which will in-turn help to improve young people’s knowledge and skills.

PISA in England offers unique opportunities in this area.

It collects rich information about Year 11 pupils and the schools they attend through the background questionnaires.

Moreover, as PISA has been linked to the National Pupil Database (NPD), the data for England includes two measures of Year 11 pupils English and mathematics scores taken just six months apart (PISA in November/December, and GCSEs in May/June, of Year 11). This offers unique opportunities to understand the factors associated with the progress young people make during this critical school year.

Unfortunately, not enough work has exploited this data. Indeed, in general, international assessment data such as PISA is, in this country, incredibly underused.

So, although PISA genuinely has the potential to inform education research, policy and practice in England, not enough work is currently being done in this area.

4. Politics

If nothing else, continued participation in PISA may simply be a political decision.

Every OECD country currently takes part – is England really going to be the one country that decides to pull out?

It would take an incredibly brave secretary of state to make such a decision and would become a very easy target for opposition parties to criticise.

Continued participation

So, should England continue to take part in PISA?

From writing this blogpost, I have convinced myself that the answer is yes. The unique, rich data that PISA provides still, in my view, offers enough potential value to justify the resources spent.

Yet there is also an important caveat upon this response: more needs to be done to realise PISA’s true potential.

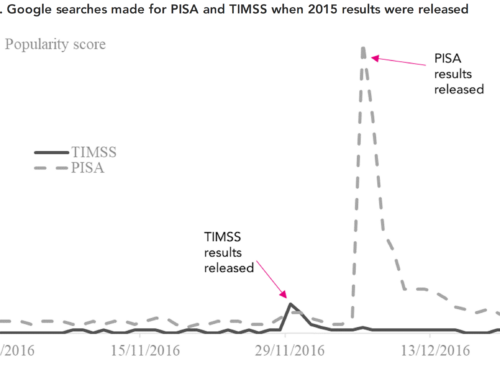

The rankings published by the OECD every three years are, frankly, no longer interesting.

The real value of PISA lies in the richness of the background questionnaire data and the link that has been made in England to the National Pupil Database. Much more needs to be done to exploit this data to start informing education policy and practise (as I have tried to start to do in my own work).

But, if this data continue to be underused, then I believe England’s continued participation in PISA will become ever harder to justify.

Want to stay up-to-date with the latest research from FFT Education Datalab? Sign up to Datalab’s mailing list to get notifications about new blogposts, or to receive the team’s half-termly newsletter.

Leave A Comment