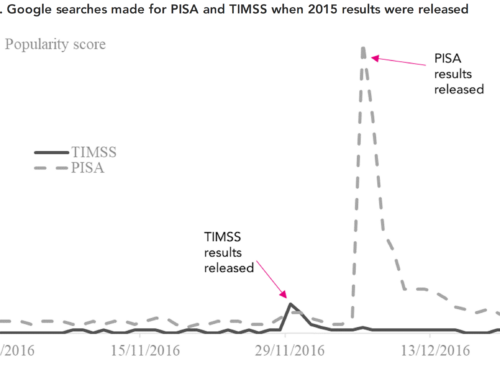

The results from PISA 2018 are released tomorrow. And, as with every PISA release, there will be the usual media circus.

There will, of course, be all the obvious things to look out for – have PISA scores for England in reading/science/maths gone up or down, are any countries doing surprisingly well/badly etc.

But, as always with PISA, the headline results are not always as straightforward to interpret as on initial inspection.

The purpose of this blogpost is therefore to flag some important things to remember when the results are released.

1. The introduction of computer-adaptive testing

From PISA 2000-2012, PISA was a standard test conducted with pencil and paper. This all changed in PISA 2015, when it moved to a computer-based assessment.

I have written previously about how this is likely to mean that the results from PISA 2015 (and 2018) are unlikely to really be comparable with those from PISA 2000-2012. Meaning we should be sceptical about how reliably PISA can measure trends over time.

But there is also the added complication that PISA 2018 has started to introduce a (crude) form of computer-adaptive testing. In other words, kids who answer the first questions correctly get harder questions as the test moves forward.

This, of course, changes the dynamic of the test in many subtle ways. For instance, the classic exam technique of skipping past a question that has you stumped and returning to it at the end is no longer possible.

Needless to say, we should be keeping a close eye on how this change to the test design has been handle (and if comparison to previous PISA results is really possible).

If there is a big increase or decrease in England’s score when the results are released, I am not sure how much faith I would place upon the results.

2. Has England hit the required response rate?

In order for countries to be included in the PISA results, enough of the sampled schools (and pupils) must be willing to participate and take the test. It is a little-known fact that England has failed to meet these criteria in four of the six PISA cycles reported on thus far (the exceptions being PISA 2012 and 2015).

While a low response rate doesn’t automatically mean that a sample is biased there is a need to check this, and England has therefore routinely had to conduct what is known as a ‘non-response bias analysis’ to illustrate that the sample is robust.

However, as I explain in my recent paper [link, PISA Canada paper], these procedures are not open and transparent and do not inspire particular faith in the quality of the PISA sample. Indeed, even in PISA 2015 (when the UK sample was as good or even better than it had ever been before) around one-in-three 15-year-olds in the UK was not covered by the test.

We’ll have to see what the response rate is, but there could be problems with the UK’s PISA 2018 sample.

We should therefore keep an eye out for whether each of the four constituent countries of the UK has had to do a non-response bias analysis – and whether the results of this analysis are clear and transparently reported.

3. Don’t be surprised when Vietnam does really well

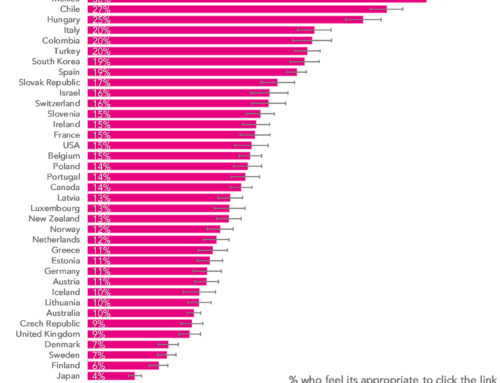

Vietnam is one of those countries that always pops-up towards the upper-end of PSA, performing better than England in science (and equally in mathematics) in PISA 2015.

But as I have written before, Vietnam’s strong performance is a classic example of a PISA mirage.

By the time the PISA test has been conducted, half of Vietnamese 15-year-olds have already left school. And those kids who drop out are typically lower-performers. So Vietnam’s strong performance should come as no surprise given that they are just testing the cream-of-the-crop!

4. Don’t get sucked in by rankings. Or even ‘statistically significant’ differences

The media always reports PISA results in terms of country rankings. But these are obviously problematic – the difference between 15th and 25th place can be so small to be negligible. Likewise, with countries joining and leaving PISA each cycle, a country can move in the latest rankings even when absolutely nothing else has changed.

But we should also not be relying upon just “statistically significant” differences either. Why?

Firstly, in large, well-powered samples like PISA, even quite small differences (in terms of magnitude) can end up becoming labelled “significant”.

Second, several countries now draw much bigger samples than others. Hence it is harder for a difference between England and (for instance) Ireland to be statistically significant than (for instance) a difference between England and Australia.

Finally, it leads to countries being unhelpfully placed into three groups (below England, same as England, above England) without given due respect to the magnitude of the differences.

My own rule for interpreting PISA results, which I tried to bring into the last PISA report [PDF] is that the point to start getting interested is where there is a difference between countries or over time of roughly 10 PISA test points (effect size of 0.1) – which the OECD approximates to be equivalent to four months of schooling – or more.

5. These are children who have been at school throughout the era of austerity

Finally, not so much a point about methodology but an interesting quirk with the data. The PISA 2018 cohort would have been born in 2003 and started school around 2008 – the time of the financial crisis.

Their period at school thus also lines up with the age of austerity and government cuts. Not to mention the significant reforms that have been made to GCSEs over this period. Indeed, they are the first PISA cohort to be taking all their GCSE examinations under the new 9-1 grading system, without coursework and under the new curriculum.

Of course, PISA can’t really tell us anything about the cause and effect of any of these individual matters. But this may nevertheless be important contextual information to think about when considering the latest PISA results.

Want to stay up-to-date with the latest research from FFT Education Datalab? Sign up to Datalab’s mailing list to get notifications about new blogposts, or to receive the team’s half-termly newsletter.

Leave A Comment