With many pupils returning to school this week for the first time since March, we will soon get an idea of quite how much learning has been lost.

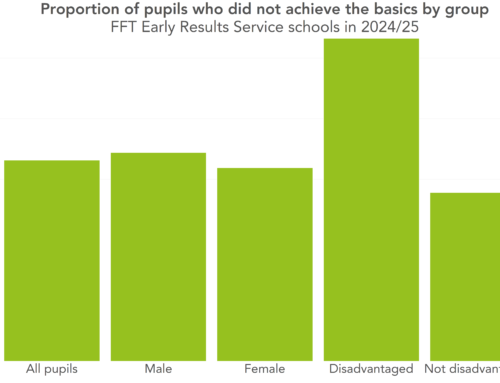

But, as we all aware, there were sizeable differences in the attainment and progress of different pupil groups even before the pandemic struck.

We know, too, that there can often be an interaction between pupil characteristics. See, for example, Mike Treadaway’s blogposts on the interaction of disadvantage status and ethnicity.

In some cases, concerns we have about educational outcomes might lessen when we focus on a smaller subgroup: the GCSE attainment of black girls as a group is higher than that of black children overall.

In other cases, they increase.

The Department for Education routinely publishes statistics on performance at age 11 and 16 broken down by pupil characteristics.

But one thing that I have been conscious of for some time is that these published statistics generally report on a limited number of pupil characteristics at a time: the attainment of disadvantaged boys, but not always of disadvantaged Asian boys.

To try to fill this information gap, I’ve produced figures on the interaction of a number of pupil characteristics for a range of Key Stage 2 and Key Stage 4 performance measures – visualised in the interactive chart below.

It allows you to explore the interaction of gender, disadvantage, ethnicity, English as an additional language (EAL) status, and whether a pupil lives in a coastal area or not.[1] Note that it uses 2019 results, so is the state of affairs pre-Covid.

Among the things we’ve spotted in the data are the following points.

Commission us

We are a team of expert analysts of education data. We use our skills to produce impactful reports, visualisations and policy recommendations.

If you have data requirements or a research project that we can help with, find out about commissioning us.

Disadvantaged, white, non-EAL boys have the lowest Key Stage 2 reading, writing and maths attainment – but those in that group who live in coastal areas have marginally higher attainment (44.9% at the expected standard) than those living in non-coastal areas (42.4%). The same is not true at Key Stage 4.

The range of KS2 maths progress scores achieved by the subgroups covered here is far greater than that of reading or writing: a spread of 9.6 (from -2.0 to + 7.6) for maths, compared to figures of 3.7 and 5.7 for reading and writing respectively.

And of the subgroups covered here, 27 non-EAL subgroups have negative Progress 8 scores and 29 non-EAL subgroups have positive Progress 8 scores. But that compares to only eight EAL subgroups with negative Progress 8 scores, and 52 with positive Progress 8 scores.

These are simply three things that we’ve spotted in the data, but do explore it yourself and let us know in the comments section below anything of interest that you spot. As well as the interactive chart, we are making the underlying data available here.

Want to stay up-to-date with the latest research from FFT Education Datalab? Sign up to Datalab’s mailing list to get notifications about new blogposts, or to receive the team’s half-termly newsletter.

1. We define coastal as living within 5.5km of the sea.

Any similar dat for post 16 GCSE maths and or Adult access ?

It would certainly be possible, Geraldine – we can have a think about making other versions in the coming weeks.

The comments for non coastal pupils read as if they are referring to coastal pupils?

Thanks for pointing this out, Steve – well spotted. I’ve fixed this now.

A fantastic resource – looking forward to a set of data for Post-16 if it is produced

Philip,

This is a really useful blogpost. The lack of ‘good data’ available nationally undermines the work of some schools in areas of a particular demographic make-up. Areas that are primarily made up of white British ethnicity, with a high proportion of long term disadvantaged pupils. This post goes some way to addressing the data gap that exists nationally.

It is not always possible to see the impact that schools in these areas are really having as like for like comparisons are not possible. It would be useful to see what this the trends are when long term disadvantage is added to the mix.

I wouLd be interested to know how you arrived on the order that the categories fall in (ie Gender, Disadvantage, Ethnicity, EAL, Coastal)? Is this in terms of a measure of the size of the “effect” of these on outcomes?

Hi Ian, thanks for your query. It doesn’t follow such an ordering – the choice of order was mostly informed by the order typically used by official figures, which itself probably has something in common with the frequency with which users use each of the breakdowns. You could reasonably make the case to order things by the size of the effect they have – I think that would also have shown some interesting patterns.

Informative article – thanks. Is there a reason for not including a layer that further separates the ethic groupings into sub-groups, e.g. Black Caribbean and Black African? There are often marked differences in educational attainment in different subgroups – Black African pupils on average have higher attainment than Black Caribbean, and further grouping shows that Black Nigerian pupils exceed the national average, contrary to the frequent narrative that labels all Black pupils as lower attainers.

Hi Steve, thanks for the comment.You’re exactly right that these major ethnic groupings disguise a lot of variation underneath – I think I’m right in saying that the composition of the population of black schoolchildren is shifting more towards being majority black African, away from being majority black Caribbean, and that if we only look at attainment at the major ethnic group level then we overlook stalled progres in improving the attainment of black Caribbean pupils. In the case of this visualisation, though, there was a limit on how much I could cram in. Adding another layer, with only two sub-groups, would have led to a doubling of the number of nodes in the bottom layer, which would have been hard to fit on a screen. It’s definitely a topic that we should, and will, return to though.