The Children’s Commissioner announced this week that she would be investigating children who have “fallen off the radar” during lockdown.

Although this is welcome, getting any sense of which children this includes and how many of them there are will be difficult for a number of reasons.

What is meant by “fallen off the radar”? It seems to me that two different things are being conflated:

- pupils who are on roll at school but who are severely absent; and

- pupils who are not on the roll of a school

From an interview given by the Commissioner to BBC Women’s Hour, it would seem that this is intentional.

Let’s look at each in turn.

Pupils on roll

Throughout the pandemic, references have been made to 100,000 “ghost children”.

This figure has been investigated by Full Fact. The origins of the number are a report by the Centre for Social Justice in which they re-analysed published absence data for the Autumn Term in 2020. They found that 93,000 pupils missed at least 50% of sessions, excluding sessions missed due to isolation/ bubbles.

As Full Fact note, this figure is now out of date. Moreover, not all these pupils are necessarily “ghost children”. There’s nothing to suggest that schools do not know about these pupils and why they are severely absent.

But there is also a little known fact about the absence data that means that even the figure of 93,000 pupils being severely absent is misleading.

When compiling absence statistics, including persistent absence statistics, DfE base their calculations on school enrolments rather than number of pupils.

Their methodology document says there are 4% more enrolments than pupils.

This will include pupils who change schools. A pupil may have been on roll at their previous school for a short time and been absent for more than 10% of sessions but then transferred to a new school for the rest of the school year and was rarely absent. This pupil would be classed as a persistent absentee in DfE statistics on account of their absence at the previous school.

In fact, pupils who were on roll (and absent) for a single day at a school would be classed as a persistent absentee by DfE.

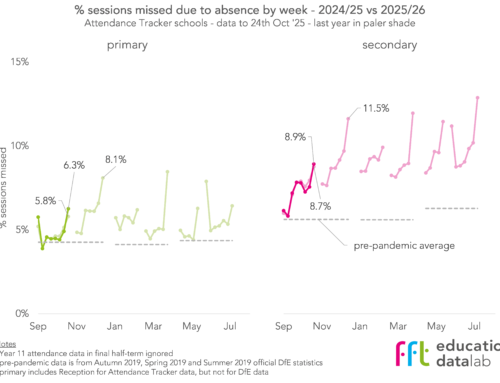

To illustrate this, let’s look at the data we’ve been collecting from schools since the start of the Autumn term this year (so Autumn term 2021 rather than Autumn term 2020). We have data from over 5,200 primary schools and over 2,600 secondary schools.

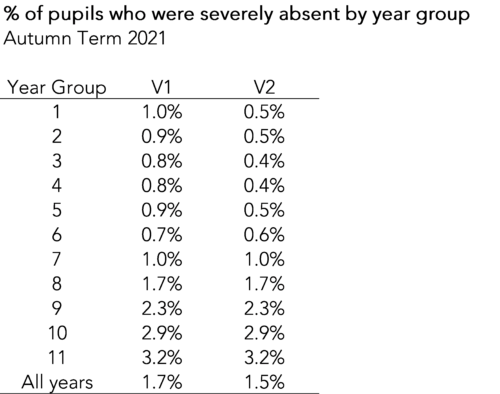

We’ve calculated the percentage of pupils in each year group who missed 50% of sessions, excluding sessions missed due to isolation[1]. We refer to this as being severely absent.

We’ve calculated two versions of the severely absent measure:

V1: based all pupil enrolments, including pupils on roll for a single day

V2: based on pupils enrolled for at least 20 days in the term

Rates of severe absence increase with age. The figures for V1 would scale up to 100,000 pupils in the national population. However, the figures for V2 would scale up to 86,000.

The reason for this is that measures that are based on aggregates (in this case twice daily attendance measures) are more variable when based on small numbers of cases (i.e. aggregates based on small numbers are more likely to have extreme values).

Nonetheless, 86,000 pupils is still a large number of pupils who are not regularly attending school for illness or other reasons.

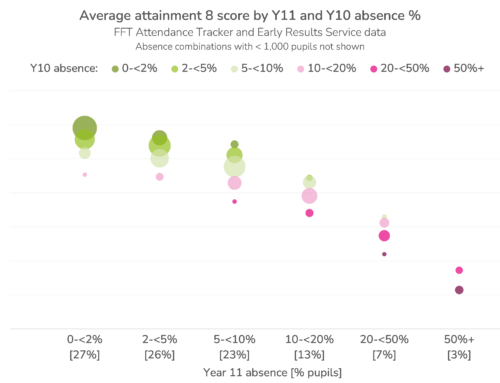

Rates of severe absence are particularly acute among pupils with special educational needs as the chart below shows.

This may be due at least in part to reduced access to services for pupils with SEN during the pandemic.

We can also quantify the proportion of young people who were on roll but who did not attend school at all last term. We limit the analysis to pupils who were on roll at their school for the whole term. 0.2% of pupils fall into this category although this varies from <0.05% in the primary sector to 0.4% among Year 10 and Year 11 pupils.

These sorts of proportions would suggest something in the order of 10,000 pupils on the roll of schools who did not attend at all in the Autumn term.

Pupils not on roll

Leaving aside pupils who reach school leaving age, some other pupils may have left the school system since the start of the pandemic.

We used school roll records for all state-funded schools in England to examine the numbers of pupils who left the system in the first part of the pandemic (up to January 2021) here.

There are four possible reasons for leaving the system: Migration (including to other parts of the UK), elective home education, transfer to the independent sector and, tragically, death. We are only able to observe pupils who leave.

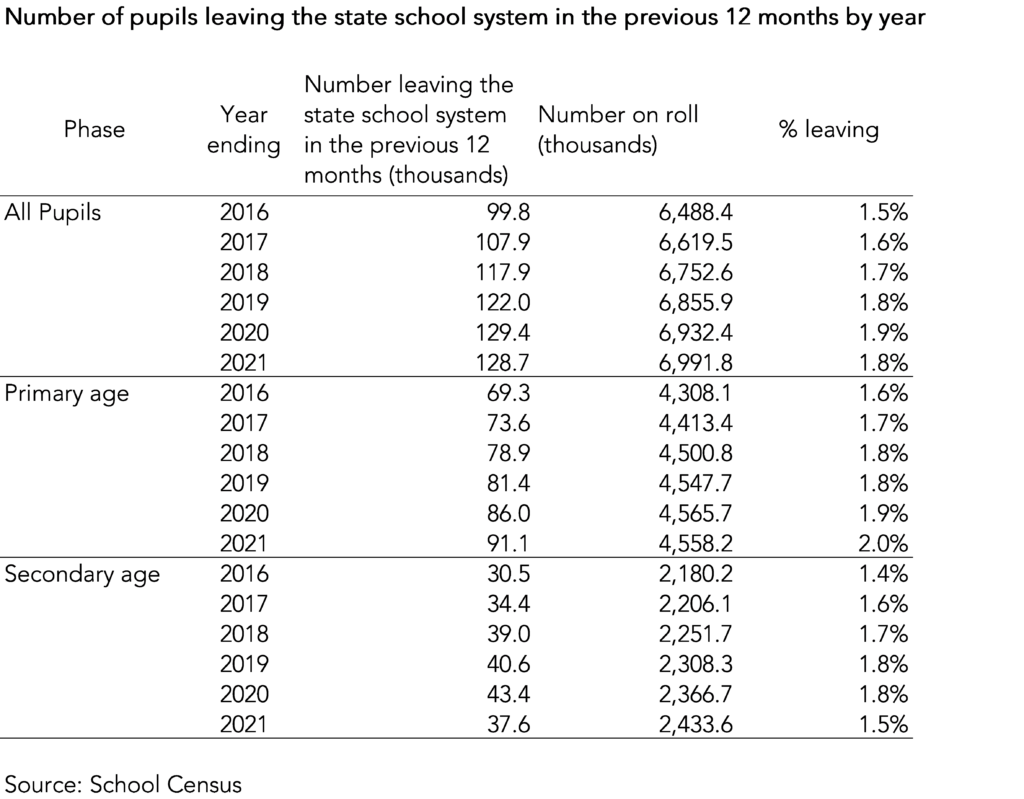

Expanding the analysis from our earlier article to all year groups, we show the percentage of compulsory age pupils below school leaving age who left the system in the previous 12 months.

Between January 2020 and January 2021, almost 129,000 pupils of compulsory school age left the state-funded school system, roughly 1.8% of all pupils. This percentage is similar to the two previous years although the data shows a slight increase in this rate between 2016 and 2020.

However, the overall figure for 2021 masks an important difference between primary and secondary schools. Whereas the rate of primary age pupils leaving the system increased, it fell among secondary age pupils.

Not all of these young people will have fallen off the radar. The Association of Directors of Children’s Services (ADCS) estimated that 57,000 young people entered elective home education. This is a perfectly legitimate choice although the Commissioner might wish to investigate why families prefer this to state-funded education.

Around 10,000 to 20,000 pupils will have moved into the independent sector.

This leaves around 40,000 to 50,000 whose destination is unknown. This will include those who leave England.

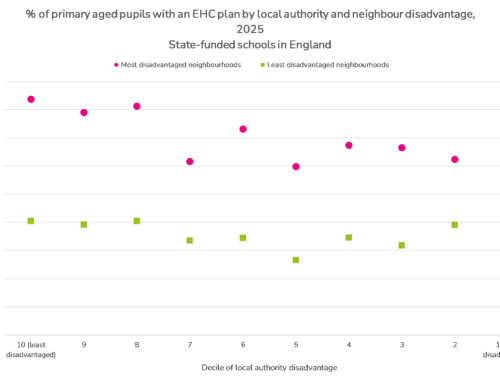

In addition, there were 1,500 young people of compulsory school age with Education, Health and Care (EHC) plans without a placement at the last time of counting in January 2021.

Add to this the growing number of young people placed by local authorities in schools and other settings outside the state-funded sector. There were over 30,000 of these at the last count.

The Commissioner may wish to find out why so many young people with EHC plans are not educated in state-funded schools.

Summing up

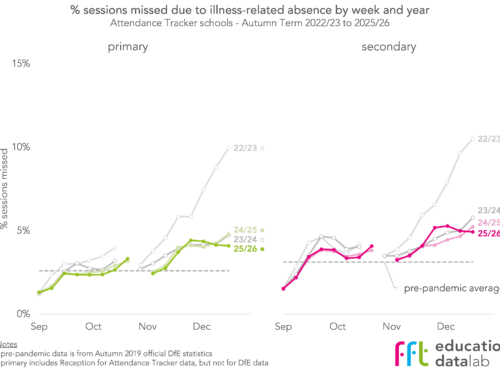

We have been living through a pandemic since February 2020 and it’s not over yet.

Some of its consequences for school-age pupils are fairly clear. They have tended to miss more school than they would have done otherwise.

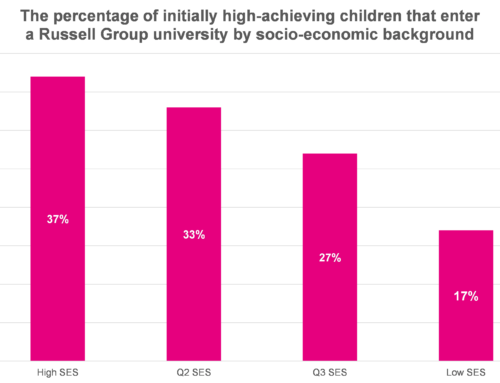

But the impact this had on their education is less clear. There were longstanding issues prior to COVID. To what extent has the pandemic made them worse? For example, there were longstanding attainment gaps between disadvantaged pupils and their peers prior to COVID but the pandemic seems to have widened them only slightly.

The Children’s Commissioner plans to investigate children and young people who are chronically absent from school and those who are not in school, home education or other provision at all. This is welcome as we don’t really have a solid understanding of the scale of these issues nor what is driving them.

These might also turn out to be long-standing issues that existed prior to COVID. But COVID may have also contributed directly (e.g. cases of long COVID) or indirectly (e.g. worsening access to services such as CAMHS).

- In other work, we have included isolation sessions in our measures of persistent absence. We exclude them here to be more in line with DfE calculations

Want to stay up-to-date with the latest research from FFT Education Datalab? Sign up to Datalab’s mailing list to get notifications about new blogposts, or to receive the team’s half-termly newsletter.

Leave A Comment