In England – as in many countries – there has been long-running challenges with recruiting and retaining enough teachers.

During my recent secondment to Ofsted, we undertook a “proof-of-concept” study matching data from the School Workforce Census back to teachers’ school and university records to provide new insights into this issue.

The data focused on a single school cohort who sat their GCSEs in 2011. For this group, we can observe where they studied at university, whether they went on to work as a teacher and (if they did) whether they were still working as a teacher up to 2021.

The academic working paper has been published today. In this blog, I focus on one finding from this study – that young people who live at home while an undergraduate are more likely to become a teacher than those who move out of the family home.

Living at home as an undergraduate and becoming a teacher

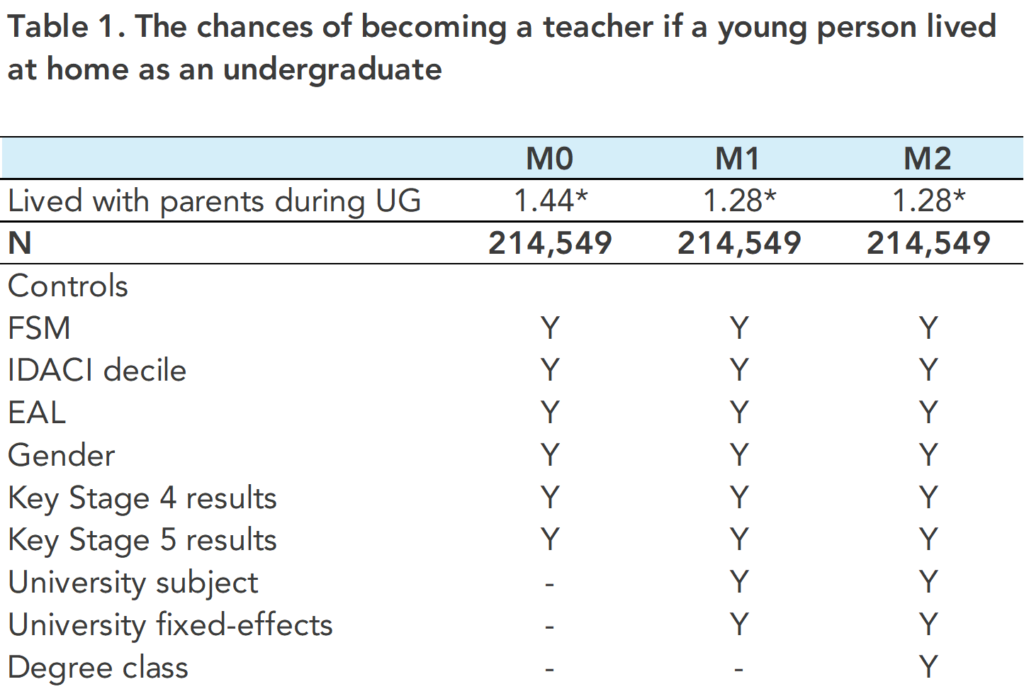

Table 1 summarises results from our logistic regression models.

The value of 1.44 in the M0 column indicates that – if a young person lives at home as an undergraduate – they are 44% more likely to become a teacher than if they move out from home[1]. This is after we have controlled for various demographic characteristics (gender, ethnicity, disadvantage), GCSE and A-Level results.

The M1 and M2 columns illustrate how, even are controlling for university subject, precise university studied at and degree class, those that lived at home are still 28% more likely to become a teacher.

In the paper, we also illustrate how teachers that lived at home as an undergraduate are 25% less likely to leave the profession than teachers that chose to move out.

So not only are “home-birds” more likely to become teachers, they are also more likely to stay.

Why!?

The data is of limited use in understanding why we find these associations. But its quite fun to speculate…

One possibility is that teaching jobs are available – and pretty evenly spread – across the country. Those who lived at home during university graduate may want to still live locally after graduating, making teaching an attractive career.

Another possibility is that this is linked to risk aversion and financial security. One reason to live at home as an undergraduate is to avoid debt, while an attraction of teaching is it offers a steady, reliable income.

Both the above could also explain why we find higher retention rates amongst these teachers. Those who prefer continuing to live local will have fewer alternative employment options (being unwilling to migrate away from home), while the risk adverse won’t like the jeopardy that comes with changing jobs.

Implications

I can think of two important implications of the findings, regardless of what may be driving it.

First, if I am a school leader, targeting recruitment efforts at those living at home as undergraduates seems appealing. I have more chance of attracting these individuals, and they will probably stay working at my school for longer. This makes TEAL’s drive towards recruiting “homegrown” talent look pretty smart.

Second, it heightens concerns about the lasting impacts of the pandemic on teacher recruitment. With alternative employment options becoming more flexible, those who live at home during university (and wish to continue living locally when they graduate) have a wider array of opportunities available to them now than previously.

[1] Technically, the odds that they become a teacher are 44% higher. But – as the outcome measure is “rare” – this will be a good approximation for the increase in the “risk” of becoming a teacher. For most, life is too short to worry about such issues.

Want to stay up-to-date with the latest research from FFT Education Datalab? Sign up to Datalab’s mailing list to get notifications about new blogposts, or to receive the team’s half-termly newsletter.

Also lots of local Unis offer teacher training so it is easy to do whilst staying at home. As a teacher unless you get to the top you are not going to be earning a fortune so hence the stay at home. I stayed at home in the 1990s and went to nearest Uni to do degree then PGCE. I didn’t initially last very long as a teacher but came back to teaching later. Though not in a traditional school setting. I work 1 to 1 now which is a rewarding job but for LEA seriously underpaid. Would be interesting to know the age profile, how many were re-training? Guess many mature students would do that on the job.

I think there’s a third element to the Why?, albeit with some overlap with the second point above: people who are in teaching for the love of teaching will accept their vocation despite the relatively low pay vs. high responsibility. So it might be the case that it’s the future teachers deciding to be home birds, rather than being a home bird deciding who becomes a teacher.

Students basing uni choices on what is close to home, rather than what is best, may be more likely to choose a less prestigious, less well-respected uni and degree subject. This will close some doors and leave them more likely to accept (or be forced to accept) a less well-respected and less well-paid job.

Also, the reason they stay at home could be because of poor family finances. People from poorer backgrounds may be more likely to be satisfied with the sub-par pay and status that teaching provides. To them it may seem relatively well rewarded, while students with families that can fund accommodation away from home at in-demand universities are probably used to a higher standard of living, less easily impressed, and can see that teaching will not provide the middle class lifestyle they are used to.