This post was updated at 20.00 on 5 May 2017 to clarify our view of how favourable a move to one of the three alternative sets of qualifying rules described in this post would be.

With a limited number of places at grammar schools available, the 11-plus is effectively a competition between children. As with any such competition, the rules determine who has the best chance of winning.

The 11-plus test, known locally as the Kent Test, is created by GL Assessment and administered by Kent County Council. Kent children take this test in their primary schools during September, with out-of-county children taking it the following weekend. Since 2014 it has comprised both reasoning and curriculum-aligned elements, the latter of which are designed to reduce the effect of coaching.

Children are assessed in four different elements, from which three paper marks are awarded:

- A 25-minute multiple-choice paper in English, testing comprehension, spelling, grammar and punctuation.

- A 25-minute multiple choice paper in maths, with national curriculum topics that should have been covered by able children by the start of Year 6.

- A reasoning test with about 20 minutes of test time on verbal reasoning, and 4-5 minutes of test time on each of non-verbal and spatial reasoning.

- An unmarked writing exercise of 40 minutes, with 10 minutes for planning and 30 minutes for writing. This exercise is not part of the test but a headteacher panel may consider it if the child is unsuccessful at passing the test.

Each of the first three test papers are marked and scores are age-standardised, with August-born children given a higher standardised score than September-born children for the same mark. The three scores are then combined to decide whether a student should automatically be considered suitable for a grammar school according to the following rule:

- The student’s aggregated standardised score across the three papers must be 320 or above;

- The student must score at least 106 in each of the three papers.

The second criterion is critical: although 7,804 students in 2015 achieved an aggregated score of 320 or above, 2,616 of these failed to achieve at least 106 on each of the three papers.

The test is identifying children who are (highly able) all-rounders, then, rather than children with particular aptitude in only one or two areas.

Small changes in the qualifying rules alters who passes

We might ask the question: what would happen if the rules on who gets in are tweaked?

This is important, because while these are the rules that are in place at present, it hasn’t always been thus, and in the future, or elsewhere, a different set of rules could be chosen. It’s necessary to understand how this choice of rules determines who does, and who doesn’t get into Kent’s grammar schools.

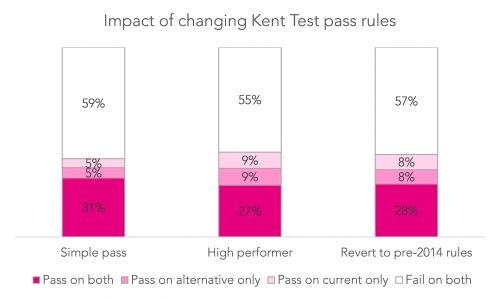

The chart below compares the status quo to three alternatives:

- A ‘simple pass’ system, where a total of 337 marks are required across the three papers, with no need to achieve a particular score in an individual paper. This is the system typically used by grammar schools in other parts of the country;

- A ‘high performer’ system, where a child must display particular aptitude in one area – achieving a score of 120 or higher in any one paper;

- The pre-2014 system – under which there was no English paper; assessment of a children’s reasoning ability accordingly making up more of the overall test.

It shows that the bulk of children would get in under neither the current system, nor any alternative being looked at. Of those who do get in under the current system, the majority would also get in under the alternative.

But there is a sizeable group of children – ranging from five to nine per cent of the total, translating into 800-1,300 children – who get in under the current system, but would not if the rules were changed, with an equivalent number of children who don’t currently get in replacing them.

That translates to between around one in seven (‘simple pass’ system) and one in four (‘high performer’ system) of those who currently pass the Kent test being vulnerable to a change in rules.

Only a minority of these children who currently fail but would pass under one of our alternatives find a route to a grammar place via the headteacher panel.

In the case of each of these three alternatives, our modelling suggests fewer children eligible for free school meals – a widely used proxy for disadvantage – would pass the test, although behaviour change would complicate the effect of a move to a different system to some extent.

We wouldn’t advocate for a move to any of these three alternatives for this reason, without fixes to other parts of the process. But all are plausible alternatives to the rules currently in place – and would have a big effect on who passed the test were they to be brought in.

Conclusion

Relatively small changes to the rules that determine whether a child has passed or failed the Kent Test would lead to material changes in who is considered to have passed the test. While other parts of the process, such as headteacher panels, lessen the impact of this, it is important to be aware how much the question of who automatically gains a place is determined by the particular rules that are in place.

Leave A Comment