We have the first set of results under the new 9-1 GCSEs

Maths, English language and English literature form the first wave of GCSEs to be reformed in England, with 9-1 numerical grades awarded instead of letters.

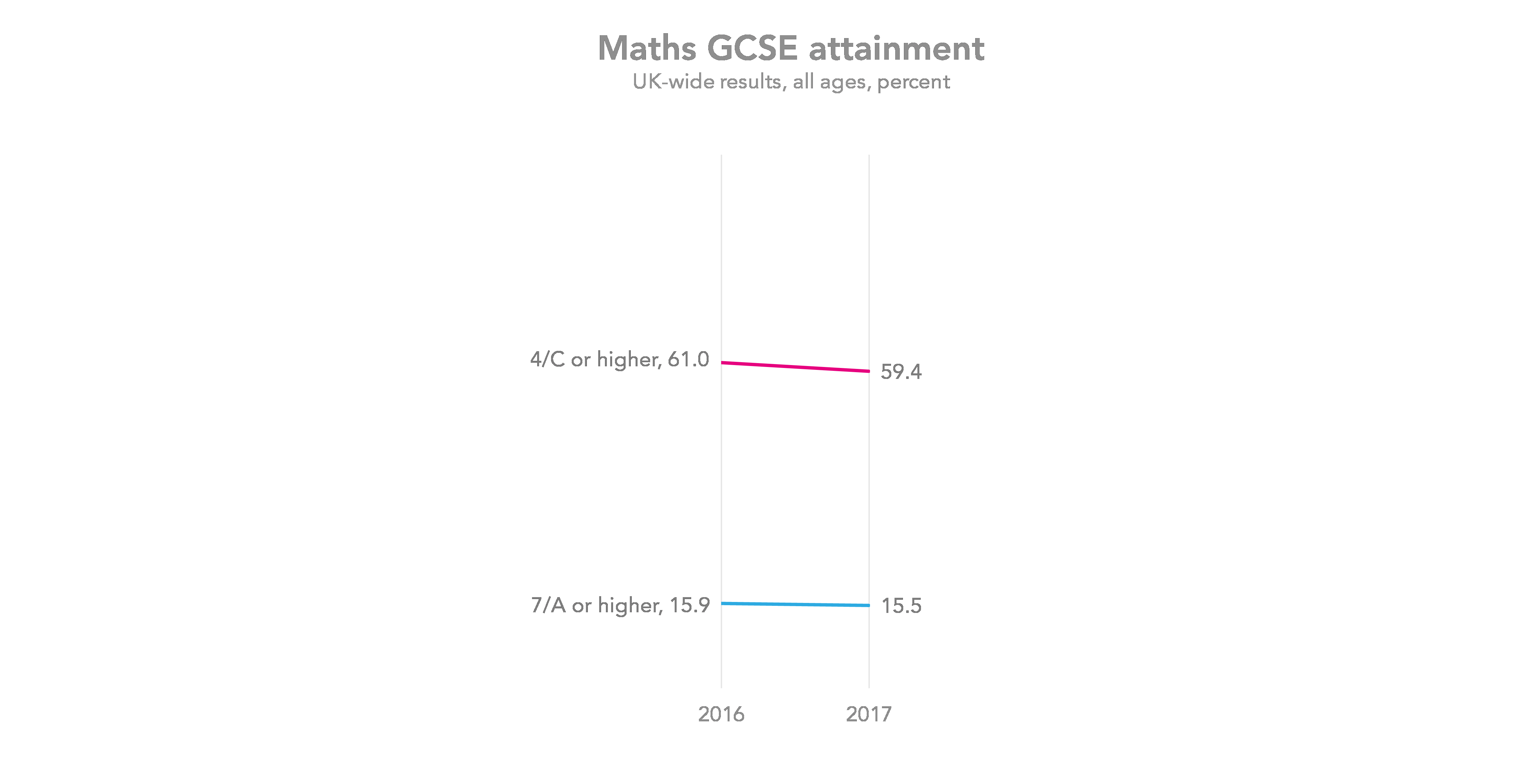

In the new, ‘fat’ maths GCSE – so-called, because of the extra content that’s been added to it – the proportion of pupils who got a grade 7/A was 15.5%, compared to 15.9% last year. The proportion who got a 4/C was 59.4%, versus 61.0% last year.

(Unless otherwise stated, figures in this post are UK-wide, though the reforms discussed affect England only. In Wales and Northern Ireland, letter grades are still used instead of numerical grades. That, coupled with resits, explains why results this year are a mix of number and letter grades.)

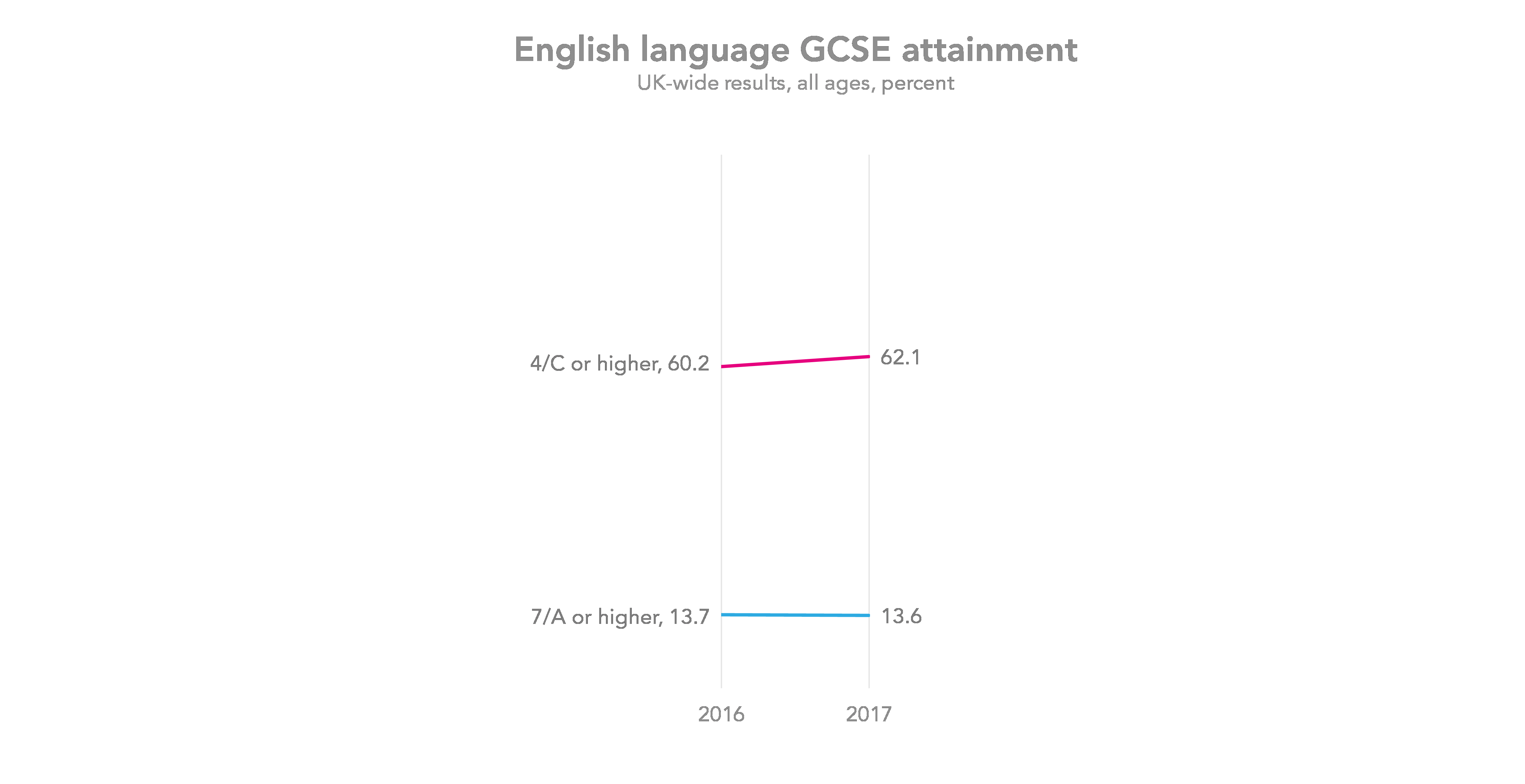

In English language, the proportion of pupils who got a 7/A was 13.6%, compared to 13.7% last year. The proportion who got a 4/C was 62.1%, against 60.2% last year.

But, unlike with the maths comparison, which we can be reasonably happy with, for English language the reality is a little more complicated than that.

There was a big increase in English language entries this year

In recent years, large numbers of pupils have been taking English IGCSES, as they have been perceived to be easier than English language GCSEs.

For the first time this year, though, IGCSEs no longer count in school league tables in England – so state schools have stopped entering pupils for them.

As a result the number of English language GCSE entries leapt this year – up 48%, from 513,000 to 760,000.

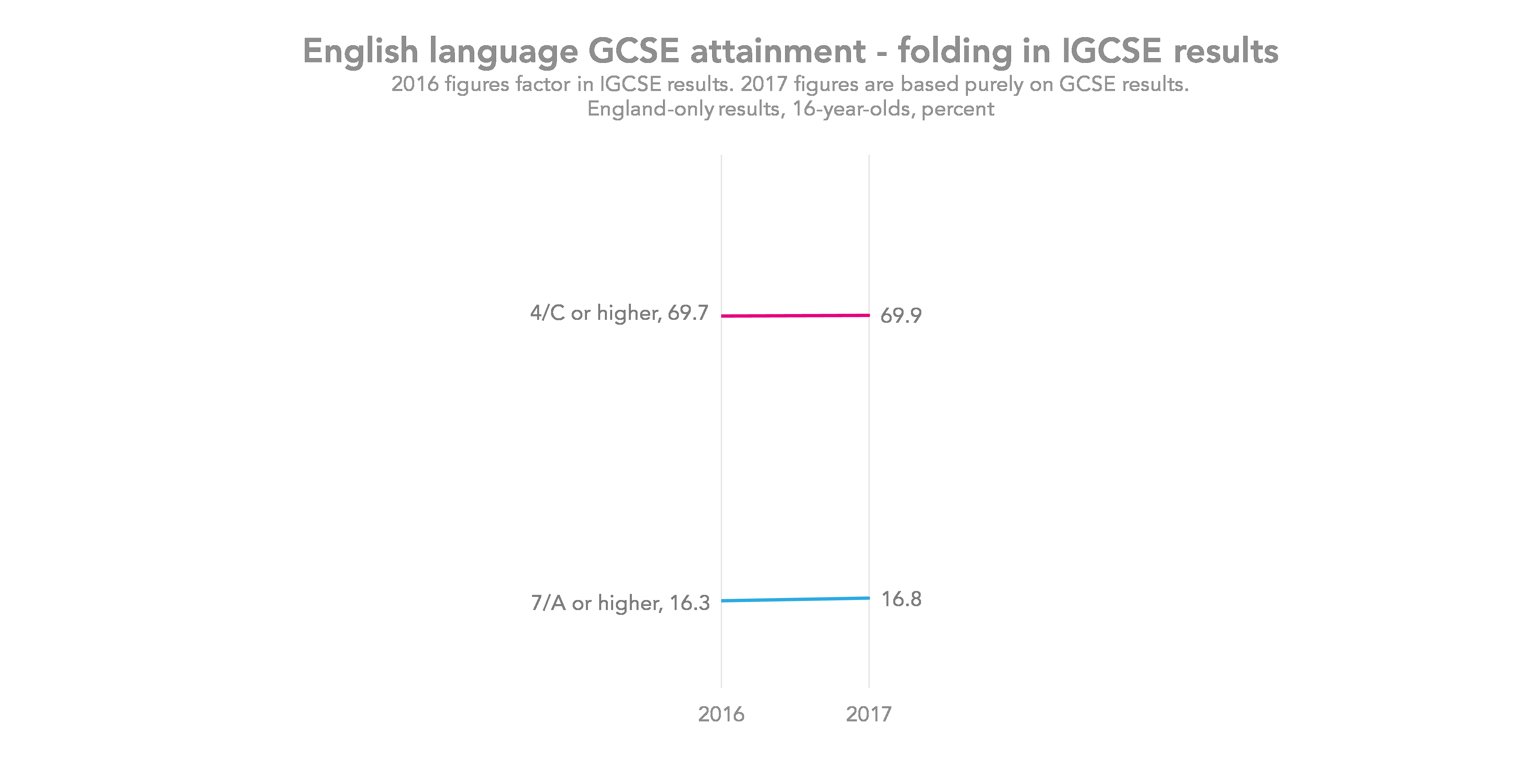

Perhaps the most meaningful comparison that can be made, then, is between combined GCSE and IGCSE results in 2016, which Ofqual helpfully pulled together [PDF], and results in the reformed English language GCSE. The former combined measure relates specifically to 16-year-olds in England, while figures on the same basis are used for this year’s results.

Comparing these, we find that this year, 16.8% achieved a grade 7 or above in English language GCSE, with 16.3% achieving an A or above in a GCSE or IGCSE last year.

And 69.9% achieved a grade 4 or above, compared to 69.7% securing a C or above in a GCSE or IGCSE last year.

These suggest that Ofqual’s comparable outcomes policy [PDF] led to some very comparable outcomes this year.

There isn’t much point trying to compare English literature results to previous years’

Two factors combine to mean the cohort taking an English literature GCSE this summer is very different to the cohort who took one last year.

Firstly, as with English language, there is a large body of pupils who have switched back from an IGCSE in English literature, now the IGCSE is no longer recognised in league tables.

Secondly, there is an effect related to the (newish) headline measure of secondary school performance in England, Progress 8. For the first time this year there is no longer a combined English GCSE, covering both literature and language. And, so, under the rules of Progress 8, in order to properly fill the English ‘bucket’ of the performance measure, pupils must now take separate English language and English literature GCSEs[1].

FFT Aspire

If you are a school using FFT Aspire, why not check your results against estimates in Aspire?

Not an FFT Aspire user?

So, this year, there will have been lots of children who will have taken a standalone English literature GCSE, who previously would have taken a combined English GCSE.

The combined effect of these has been to increase the number of English literature GCSE entries by 39% this year, from 414,000 to 574,000.

And, because it was lower attaining pupils who typically took the combined English GCSE, the introduction of these pupils has led to an apparent decline in English literature pass rates.

In English literature, the proportion of pupils who got a 7/A or higher was 19.2%, compared to 21.3% last year. And the proportion who got a 4/C or higher was 72.6%, against 75.1% last year. (These figures are higher than the respective figures for English language – as has historically been the case.)

Because, while the exams regulator, Ofqual, said that at the ‘anchor points’ of grades 7, 4 and 1, similar numbers would achieve these grades, or higher, as received grades A, C, G, or higher, respectively, under the old GCSEs, this assumed a stable entry of exam candidates.

So, where the prior attainment of candidates for a certain subject changed, it was always possible that results would change – possibly quite drastically.

The changing profile of entrants in English literature therefore means there is no real comparator for this year’s results (not even combined 2016 GCSE and IGCSE figures).

All we can say is that quite a different body of students took an English literature GCSE this year compared to last year.

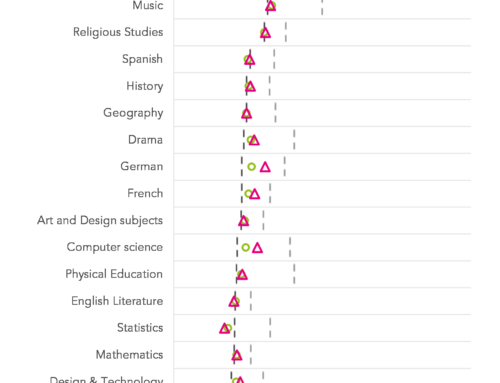

Entries in EBacc subjects are up (but really they’re down)

Overall entries in EBacc subjects appear to be up this year – but that is driven entirely by the increase in entries in English language and English literature.

Entries in the languages in particular are down sharply – something that we’ll be returning to shortly, for our second results day post. Check our homepage again shortly, or sign up to our mailing list below.

Want to receive other results day blogposts by email? Sign up to our mailing list to get notifications about new blogposts, or to receive our half-termly newsletter.

1. Under the rules of Progress 8, English is double-weighted – with the results of the higher of a pupil’s English language and English literature doubled (rather than the results in each of those subjects counting). Were a child to take only one of English language and English literature, the results would not be doubled – effectively meaning this English ‘bucket’ would only be half-filled.

Schools need some national figures on how their tier of entry decisions for maths affect the outcomes for grade 4 and grade 5 students. Is anyone pulling this together at national level? Without this schools will use ‘trial and error’ for a few years and then the ‘magic wand’ grapevine will get working…….

Hi Anne. Thanks for commenting. It’s something we’ll probably be able to take a look at later in the year when student-level data is available.

When do headline figures such as the basics usually get published?

Hi Natalie. Early October when DfE publishes is provisional statistical first release https://www.gov.uk/government/collections/statistics-gcses-key-stage-4

Is there any data available regarding the different examination boards for Mathematics and the impact this has had on pupil outcomes this year? Thank you for this.

Not yet. Unlikely there will be much difference due to Ofqual regulating the awarding process. Might be worth looking at tiers in maths as suggested by another contributor.

Thank you for this article. I have heard that if you took both English Language and Literature GCSE and obtained a grade 4 in Literature but a grade 3 in English Language as a student you could say that you had passed English and there was no need to re-sit. Can you confirm if this is correct please?

Thanks Sue. Yes, that’s our understanding based on the table half-way down this: https://www.gov.uk/guidance/16-to-19-funding-maths-and-english-condition-of-funding