Update 13:50, 10 October 2018: This post was updated to clarify that within the group referred to as always Pupil Premium exist a small number of pupils who start and end secondary education eligible for the Pupil Premium, but spend a brief period not eligible for the Pupil Premium.

A couple of readers in secondary schools have been in touch recently about pupils moving out of (and into) the Pupil Premium group and the effect that this has on end of Key Stage 4 performance measures for the group.

For secondary schools, there are essentially four groups of pupils in a cohort:

- Those who are in the Pupil Premium group when they join in Year 7, and are in the Pupil Premium group in January of Year 11. In all but a very small number of cases – fewer than 500 – these pupils have been in the Pupil Premium group for the entire period, so this group are referred to in the rest of this post as always Pupil Premium

- Those who are in the Pupil Premium group when they join in Year 7 but are no longer in the Pupil Premium group by the January of Year 11 (these are pupils who would have been last eligible for free school meals in Year 5 or earlier) – referred to as Pupil Premium leavers

- Those who are not in the Pupil Premium group when they join in Year 7 but enter the Pupil Premium group before Year 11 – referred to as Pupil Premium joiners

- Those who never appear in the Pupil Premium group – referred to as never Pupil Premium

By the end of KS4, the Pupil Premium group consists of the always Pupil Premium and the Pupil Premium joiners groups, while the non-Pupil Premium group consists of the Pupil Premium leavers and the never Pupil Premium group.

Pupils in the Pupil Premium leavers group do not count for the disadvantaged group in published performance measures (such as Progress 8) even though they will have attracted Pupil Premium funding for part of their secondary school career.

However, pupils in the Pupil Premium joiners group count the same as pupils in the always Pupil Premium group in the calculation of published performance measures, even though they will have attracted Pupil Premium funding for only a proportion of their secondary school career.

Therefore, when schools are asked to justify their Pupil Premium funding on the basis of the performance of their Pupil Premium group, the data typically used does not include all pupils who would have attracted Pupil Premium funding during their secondary school career.

But before we ask whether this is actually a problem, let’s look at some data.

Moves into and out of the Pupil Premium group

I’m using data for state-funded mainstream schools in 2017. I’ve worked out which of the four groups each pupil falls into from their free school meals history in the school census.

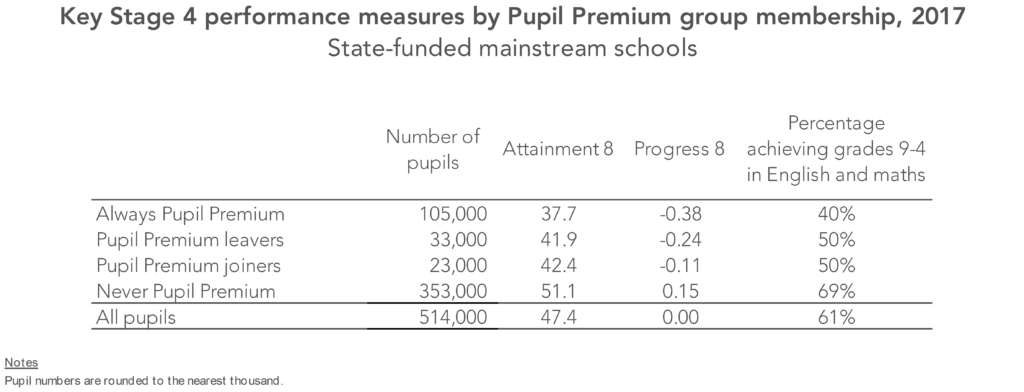

As the table below shows, at a national level, the attainment of the Pupil Premium leavers and the Pupil Premium joiners groups broadly balance out in Attainment 8 terms – but the Pupil Premium leavers group perform less well in Progress 8 terms.

Reweighting schools’ data

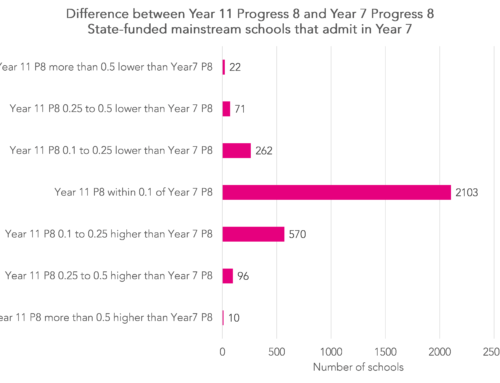

Unsurprisingly, some schools are more affected than others.

This could be avoided by including pupils in all groups other than the never Pupil Premium group when calculating school-level disadvantage measures, in proportion to the amount of time they were eligible for Pupil Premium funding. Weighting results in this way, a pupil in the Pupil Premium group all the way from Year 7 to Year 11 would receive full weighting (a weighting of 1). A pupil who was in the Pupil Premium group from the start of Year 7 until the end of Year 9 would receive 0.6 weighting (based on them having been in the Pupil Premium group for nine terms out of 15).

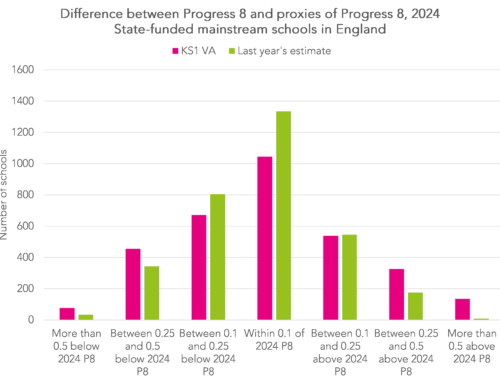

The chart below shows schools’ published Progress 8 scores plotted against the Progress 8 score they would have under this weighted approach.

As is often the case, this extra complexity makes little difference on the whole but there are exceptional cases. The Progress 8 scores of 115 schools – generally but not always with small cohorts of disadvantaged pupils – change by more than 0.25.

Final thoughts

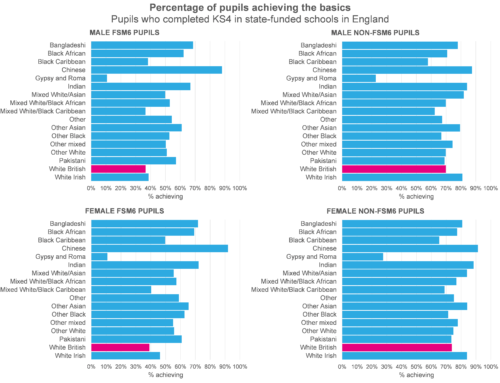

Before summarising, I ought to acknowledge that I’ve ignored the fact that there are lots of other factors that affect school-level performance measures for disadvantaged pupils – length of time in receipt of free school meals across their entire school history and other background characteristics (such as ethnicity) being just two.

Is the disconnect between Pupil Premium funding and Pupil Premium performance measures a problem? Well, it is if you’re asked to justify the former on the basis of the latter.

But is this a worthwhile thing to do? Ultimately, the Pupil Premium is a mechanism for delivering funding where it is needed the most. In her blogpost trilogy, ‘The Pupil Premium is not working’, Becky Allen sets out why schools serving disadvantaged communities need more money for dealing with safeguarding, behaviour and attendance, not just raising attainment.

Becky also suggests that we shouldn’t ring-fence the funding exclusively for eligible pupils because they may not necessarily be the lowest income or more educationally disadvantaged pupils in school.

Moreover, schools can’t know with any certainty which pupils will become eligible during their time at school. It could be argued that using Pupil Premium funding to fund high-quality teaching is therefore more appropriate than waiting until pupils become eligible and then providing targeted interventions. This seems to be the position of Kevan Collins, the chief executive of the Education Endowment Foundation.

As a result, asking schools to justify their Pupil Premium spending solely on the basis of the attainment of those who happened to be a) eligible and b) on roll at the end of Year 11 is perhaps not the best approach.

Want to stay up-to-date with the latest research from FFT Education Datalab? Follow us on Twitter to get all of our research as it comes out.

Have you missed a group out? What about pupils who started Y7 being eligible for the pupil premium, then subsequently stopped being eligible for it, and then came back into it by Y11?

Hi Stephen. Very good point. I’ve got them included in the “always” group at the moment. I’ll split them out when I get a minute. Thanks again.

This has now been reflected in the post above.

OK, if they only make up 0.5% of the “Always” group then statistically they are pretty insignificant, fair enough! I had thought there might be more in that group, but I guess those with volatile incomes will usually be backwards and forwards across the threshold more frequently than 6 years so might come off FSM and go back on, but won’t come off PP.

That’s right- you basically need a 6 year gap between periods. Still a good shout though.

Thanks for this post. It is an issue I have been battling with and nice to hear I’m not the only one. My school serves a large service population which complicates this even further for us. Although the funding is clearly different and designed to focus on pastoral support I’m not sure you can separate that from the academic performance. We do feel it unfair that they don’t count as disadvantaged or that there is some acknowledgement of the work we do to secure good outcomes for that group in performance tables.

Could you clarify on other scenario? What about pupils eligle for EVER6 in January census of Year 11, but EVER6 expires in say April, Tables checking in July they are no longer Ever6. Do they count in figures?