Our esteemed erstwhile colleague Becky Allen certainly captured the zeitgeist with her 2018 ResearchED talk and subsequent three-part blogpost on how the Pupil Premium is not working.

From the first part of her trilogy, she makes three key points about the problems inherent in making inferences based on measuring gaps, even at a national level:

- Attainment indicators change regularly and, when they do – such as with the introduction of 9-1 grades at GCSE – disproportionately favour higher attainers, and so tend to penalise the disadvantaged group.

- Free school meal (FSM) eligibility, and therefore Pupil Premium entitlement, varies due to economic cycles and changes to benefits policy, both nationally and locally.

- As I can’t say it any better, “FSM eligibility falls continuously from age 4 onwards as parents gradually choose (or are forced) to return to the labour market. This means comparisons of FSP, KS1, KS2 and KS4 gaps aren’t interesting.” I showed this here. It is why proportions of pupils eligible for the Pupil Premium are higher in Year 6 than in Year 11.

In this much less barnstorming blogpost, I would like to examine an aspect the second of these points in more detail – the changes that have occurred to free school meals eligibility this year as a consequence of benefits reforms; namely the rollout of Universal Credit.

The phased rollout of Universal Credit, following pilots in several areas, will have consequences for which pupils will be identified as being eligible for the Pupil Premium in the short-to-medium term until new FSM eligibility criteria bed in.

It appears that areas that were in the first waves of full Universal Credit rollout will have more pupils eligible for the Pupil Premium than they otherwise would have done.

Changes to free school meals eligibility

From its early pilot days until recently, any Universal Credit claimants with children were automatically deemed eligible for free school meals.

But the criteria for free school meals eligibility were changed in April 2018 for new claimants of Universal Credit. The Department for Education had earlier consulted [PDF] on the changes and what they would mean for schools.

Under the new free school meals eligibility criteria, only households with net incomes (i.e. excluding benefits) of £7,400 or under are eligible.

However, to avoid pupils missing out on free school meals as a result of the changes, the DfE has chosen to ‘protect’ the children of existing claimants, even if they no longer meet the eligibility criteria. These transitional arrangements will remain in place in two phases. Firstly until Universal Credit has been fully rolled out nationally (expected to be March 2022) and then until a pupil reaches the end of the phase of schooling (Year 6 or Year 11) that they are in at the time.

The rollout of Universal Credit

To keep the number of words down to a reasonable level, I’m going to gloss over a lot of detail about what Universal Credit is and how it was rolled out. In short, it replaces six means-tested benefits for working age adults, and began to be rolled out in certain areas from April 2013.

At first, it was rolled out to groups whose claims were simple to manage: mainly single, childless, out-of-work adults with no housing costs.

It wasn’t until November 2014 that claims from couples with children and lone parents began to be accepted in Warrington and Wirral. This was extended to the rest of north-west England and a handful of Jobcentre areas elsewhere in England (Hammersmith, Bath, Rugby, and Harrogate), plus one in each of Wales and Scotland in 2015.

(If you’re particularly interested you can read National Audit Office reports on the early rollout here [PDF] and something more current here [PDF]).

The impact of the introduction of Universal Credit in pilot areas

In pilot areas, Universal Credit was rolled out through individual Jobcentres. These serve areas defined by postcode sectors (e.g. the postcode sector of SW12 8LS is SW12 8). As we don’t have postcode (or postcode sector) in the pupil data we are permitted to use for research, we cannot link pupils to specific Jobcentres.

We can, however, assign them to the local authority district in which they live, and treat the entire local authority district with a pilot Jobcentre as being a pilot area. For example, the Hammersmith Jobcentre participated in the pilot so we treat the London Borough of Hammersmith and Fulham as a pilot area even though other Jobcentres in the borough (Shepherd’s Bush and Fulham) were not involved. This is a limitation of this analysis.

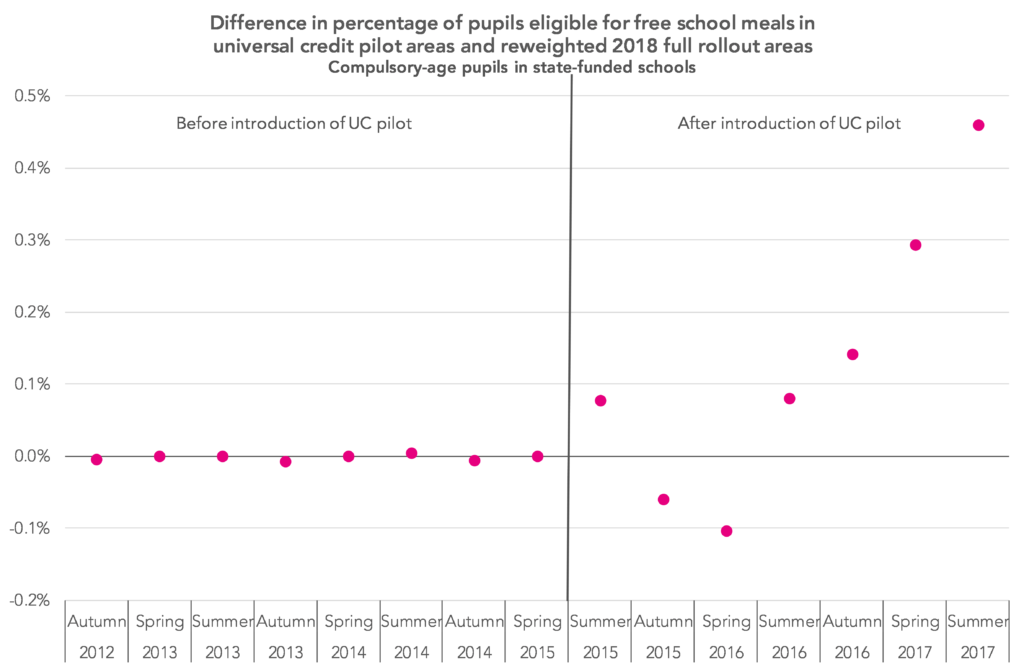

To examine the impact of Universal Credit on free school meals eligibility we can compare what happened in pilot areas to areas that were unaffected by Universal Credit until 2018.

Prior to the introduction of Universal Credit, free school meals eligibility was higher in pilot areas than areas in our comparison group. In spring 2014, for example, it stood at 19.3% in pilot areas and 16.9% in 2018 rollout areas.

To make the two groups more comparable, I’ve reweighted the 2018 rollout area average, based on FSM rates and area characteristics.[1]

Compared to areas unaffected by Universal Credit until 2018, free school meals eligibility in the pilot areas initially fell fractionally and then increased slightly after the spring school census 2015. By summer 2017, the FSM eligibility rate had increased by almost 0.5 percentage points compared to spring 2015.

The impact of the full implementation of Universal Credit

Implementation of the full Universal Credit service began in November 2015 and is expected to be completed by the end of 2018.

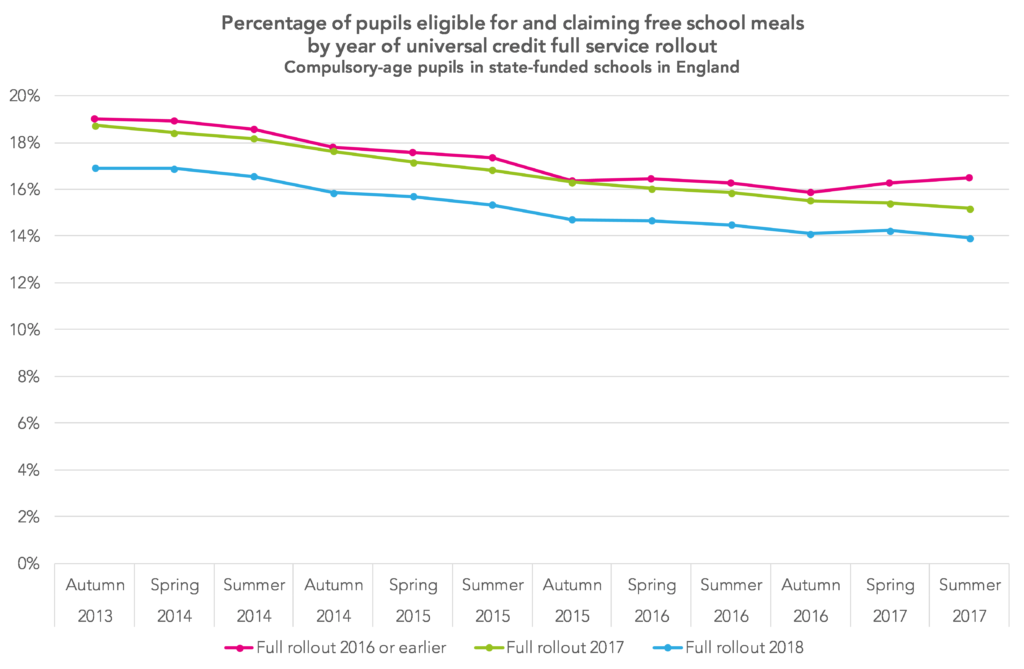

Free school meals eligibility has increased in areas in which Universal Credit was rolled out earlier in the cycle compared to those scheduled for implementation in 2018.

The chart below shows that free school meals eligibility increased during the 2016/17 academic year in local authority districts in which Universal Credit was rolled out in the 2016 calendar year or earlier.

In other areas, free school meals eligibility continued to decline or began to plateau, following several terms of successive decline. (Pilot areas have been excluded from this chart).

Final thoughts

So, what conclusions can we draw from this?

The early introduction of Universal Credit tends to have increased free school meals eligibility in affected areas. We cannot be absolutely certain, but there are probably more eligible pupils than there otherwise would have been in these areas.

These areas are likely to be winners for the medium term in two regards. Firstly, they are likely to receive more funding for disadvantage (e.g. through the Pupil Premium). Secondly, attainment statistics for the disadvantaged group are likely to be boosted by the inclusion of less-disadvantaged pupils.

Want to stay up-to-date with the latest research from FFT Education Datalab? Sign up to Datalab’s mailing list to get notifications about new blogposts, or to receive the team’s half-termly newsletter.

1. Reweighting is on the basis of free school meals eligibility rates up to and including spring 2015, and some measures about the population in each area (percentage of population in professional occupations, population density, percentage of population from non-white ethnic backgrounds, and percentage of lone parents).

A brilliant piece of analysis. Do you have any thoughts on whether it’s possible for the DfE to somehow identify the people getting FSM who shouldn’t be, so that they can remove them from the data and ensure FSM/PP data is comparable? I suspect this is impossible from the currently available data – but is there even a way to do it by collecting more data from somewhere?

Hi Ben. Thank you very much! I’m not sure it could be done with any certainty although DfE have had a go at doing something https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/707466/Additional_free_school_meal_pupils_under_Universal_Credit.pdf and then IFS had a go at replicating their calculations https://www.ifs.org.uk/uploads/publications/bns/BN232.pdf