There has been plenty of attention on the number of pupils eligible for the Pupil Premium as a result of being eligible for free school meals (FSM) in the past six years.

But there have been some interesting changes in recent years to free school meal eligibility as a result of changes to state benefits, particularly the introduction of Universal Credit.

In this blogpost we’ll take a look at some of these changes and think about the impact they might have for identifying the long-term disadvantaged group.

Changes in FSM eligibility

Let’s start off by summarising free school meal eligibility using the January School Census from 2014 to 2021. We just include pupils in Reception to Year 11.

The chart below shows four lines:

- The percentage of pupils eligible for free school meals in the last 6 years (FSM6) which attract funding through the Pupil Premium

- The percentage of pupils eligible for free school meals on census day, which are a subset of the above and broken down into:

- Recent claimants (started a period of FSM eligibility in the last year)

- Continuing claimants (eligibility started more than a year ago)

Between 2014 and 2018, the percentage of pupils eligible for and claiming free school meals fell. However, it has been increasing since then.

It can be seen that there has been a sharp increase in continuing claimants since 2018. This was when changes to benefits were introduced (see below).

By contrast, the percentage of recent claimants continued to decline until 2020 but has increased since the start of the pandemic.

The overall effect on the FSM6 group has been marginal. The rate fell from 28% in 2014 to 25% in 2020 increasing to 26% in 2021.

The impact of benefits changes

I’m not going to go into the mechanics of Universal Credit (UC). Suffice to say it was meant to replace six means-tested benefits. It has been rolling out (slowly) since April 2013.

The criteria for free school meal eligibility were changed in April 2018 for new claimants of Universal Credit. Whereas UC claimants with school age children were previously eligible to claim free school meals, an income threshold was henceforth imposed.

However, protections were also in put in place while UC continued to be rolled out. Pupils eligible for free school meals in April 2018 (and those who subsequently became eligible) would continue to be eligible until at least March 2022 when UC was expected to be fully rolled out (spoiler alert: it still hasn’t been).

We’ve shown before how the chances of experiencing free school meals decline as pupils get older. Consequently, we would have seen in the past pupils ceasing to be eligible for free school meals from one year to the next.

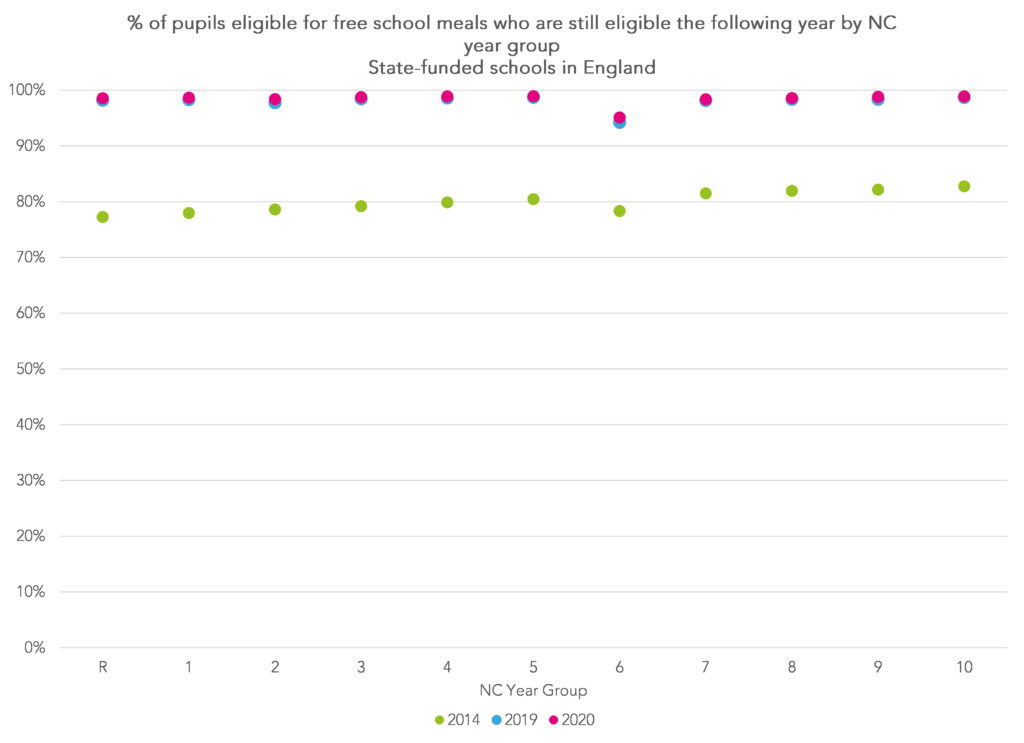

In the chart below, we show the percentage of pupils eligible for free school meals in each year who are still eligible the following year.

The green dots show the pattern for 2014 to 2015 prior to the benefits changes. Around 80% of FSM pupils in 2014 were still eligible in 2015.

The puce and blue dots show the situation for the last two years. As can be seen almost all claims continue, with a noticeable dip in Year 7 when most pupils will have changed schools. In fact, due to protection of free school meal eligibility, these figures should all be 100%.

The impact of universal infant free school meals

Universal infant free school meals have been in place since September 2014.

This has led to lower take-up of free school meals in the infant years (Reception to Year 2) as the chart below hints.

Primary schools miss out on Pupil Premium funding for these pupils until they register for free school meals. Some pupils may miss out on subsequent funding because they are no longer eligible beyond Year 2.

We had a go at working out how much funding primary schools were missing out on as a result of universal infant free school meals a few years ago.

The Pupil Premium group in secondary schools is going to grow

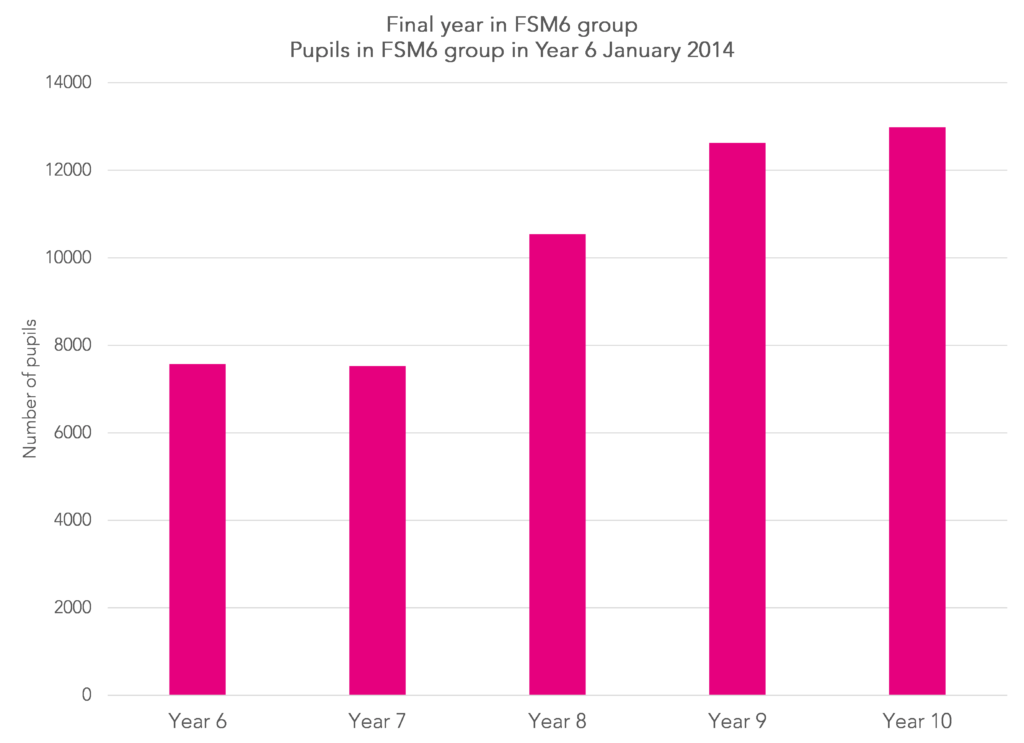

In the past, pupils who were eligible for FSM at primary school in the summer of Year 5 or any time during Year 6 would remain in the Pupil Premium group until Year 11. But pupils who were eligible earlier in their primary school career would cease to be funded six years after last being eligible. For example, a pupil who was eligible in the Summer term in Year 1 but not thereafter would remain in the PP group until Year 7 but not beyond. We wrote about flows into and out of the FSM6 group here.

The chart below illustrates this. We track the 172,000 pupils in the FSM6 group in Year 6 in 2014 through to the end of Year 11 in 2019. 121,000 (70%) were in the FSM6 group in Year 11. The remaining 51,000 dropped out of the group in the intervening years as shown in the chart.

Now, however, any pupils eligible for free school meals currently in primary will have their eligibility protected until they reach the end of primary school. This means that they will remain in the FSM6 group until they reach the end of secondary school.

So, for example, all of the 168,000 FSM6 pupils in Year 3 in 2021 will remain in the FSM6 group until the end of secondary unless the funding rules change.

The long-term disadvantaged

We’ve been saying for a long time that long-term disadvantaged pupils should attract greater funding, particularly in secondary schools.

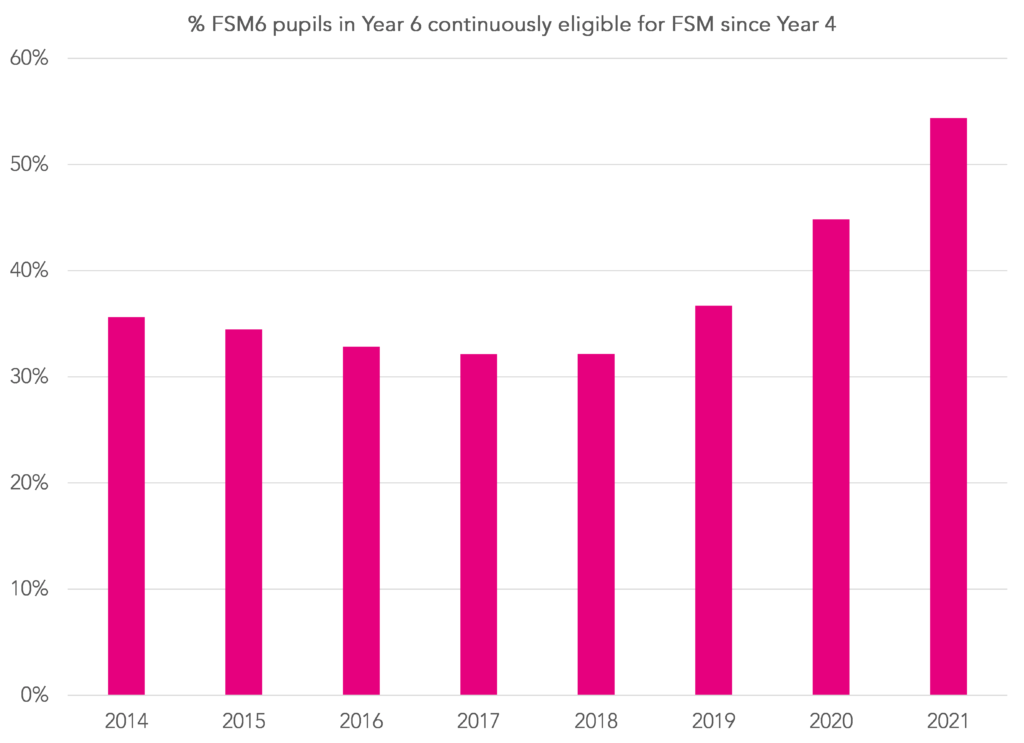

Up to now we’ve used a measure based on the percentage of terms a pupil is identified as FSM from Reception onwards. Those who have spent at least 80% of terms eligible for FSM we have classified as long-term disadvantaged.

However, this measure will become less meaningful over time as pupils remain eligible for free school meals due to protection rather than financial circumstances.

The chart below shows the percentage of pupils in the Year 6 FSM6 group who were eligible for FSM every term since the start of Year 4. It can be seen that this figure is highest for the 2021 cohort who would have started Year 4 just after the benefits changes were introduced.

We therefore need a better measure of long-term disadvantage.

DfE managed to get some way towards linking pupil data to parental income data. However, this seemed to get co-opted for political sloganeering about “ordinary working families”. This was a shame as it had potential to identify the group of pupils most in need of support within the education system.

So we’ve seen that patterns of free school meal eligibility have changed due to both changes to eligibility criteria and the pandemic. This will have knock-on effects for Pupil Premium funding over many years and also for analysis based on measures of disadvantage, including measurement of the attainment gap. Sadly, it might also scupper any plans to distribute Pupil Premium funding more equitably based on length of time in receipt of free school meals.

We’ve already seen DfE change its methodology for funding the Pupil Premium in the face of increased numbers of eligible pupils. How will it react when faced with this in future?

Want to stay up-to-date with the latest research from FFT Education Datalab? Sign up to Datalab’s mailing list to get notifications about new blogposts, or to receive the team’s half-termly newsletter.

Really interesting numbers expecially y6-7. Added to the phase change may be how rigorous schools are at ensuring eligibility when applying FSM. eg secondary require online checker / can afford to pay for online facility vs smaller staffed primary looking at paper records / listening to real hardship cases. We have some who have been FSM in y6, (DFE records) but not eligible when checked online 🙁