In the first part of this series on the London effect, we showed that the difference between London and the rest of England is not entirely explained by ethnicity. Here, we’re going to delve a bit more deeply into how the London effect affects different groups of students.

We should start by saying that we don’t really think it is a London effect. For a start, it can be found in Birmingham too.

Secondly, as we’ll show, some groups of pupils in London don’t seem to be affected by it at all.

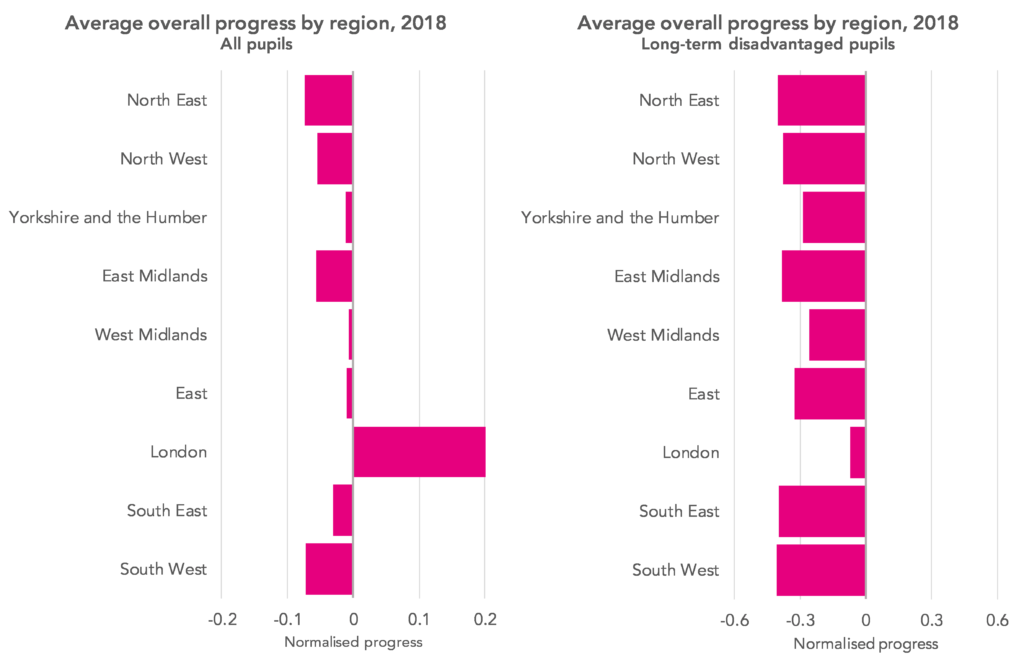

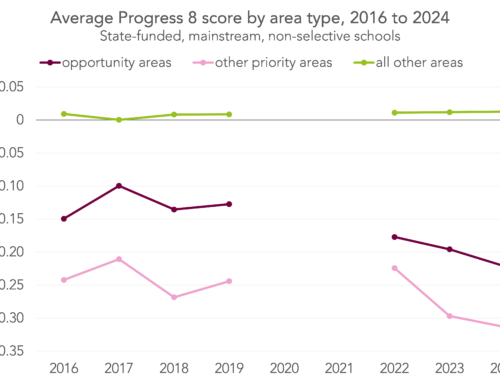

Starting by looking at the progress of all students by region, using the same overall progress measure used in the previous post – again, normalised to put it on a common scale – as the chart below shows, the London effect is obvious. It’s still obvious if we just look at long-term disadvantaged students – defined here as being students who have been eligible for free school meals for more than 80% of their school career

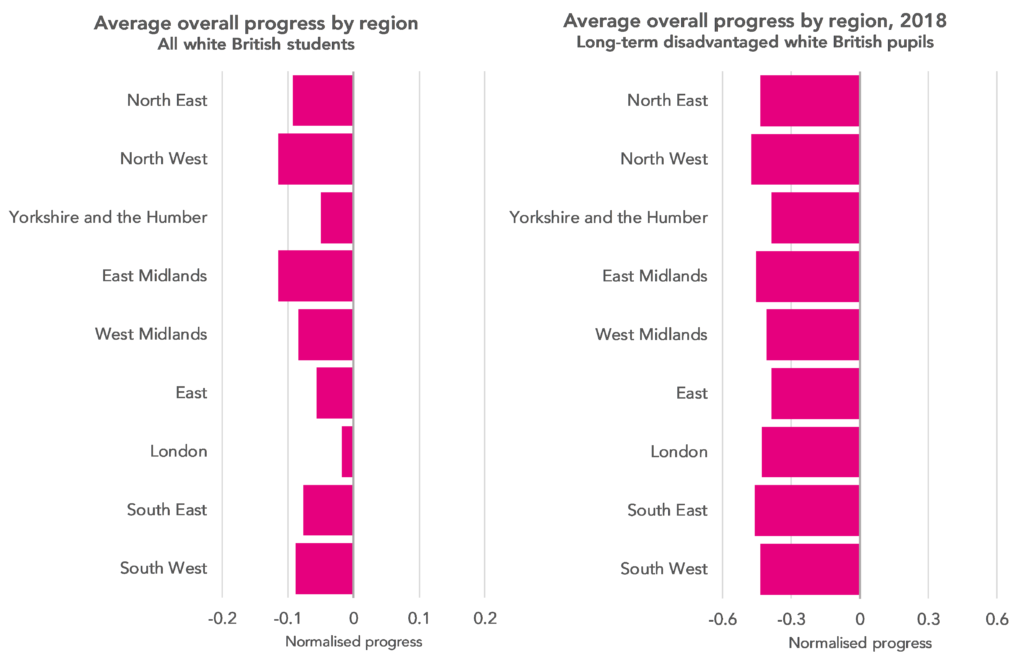

However, if we look just at white British students the picture is very different. While overall, white British students do slightly better in London than elsewhere, the effect disappears for long-term disadvantaged students, as the next charts show.

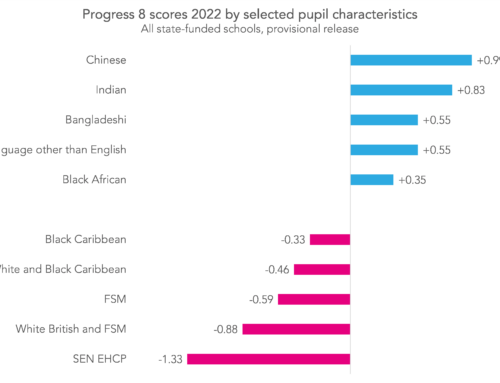

This isn’t surprising. We have previously written about “high impact groups” – those students for whom being disadvantaged appears to have the most impact, such as black Caribbean, mixed white/black Caribbean and white British students. The majority of those in this high impact group are white British students. And we’ve shown that these students do not seem to make any more progress in London than elsewhere.

High impact disadvantaged groups

In London, 12% of pupils were classified as disadvantaged and within a high impact group in 2018, compared to 19% in the rest of England (and up to 28% in the north east). So could the London effect be explained by the fact that London has a lower proportion of these students when compared to the rest of England?

Well, not entirely. In the first part of this series, we talked a lot about the analysis that Simon Burgess carried out for his 2014 paper on the London effect.

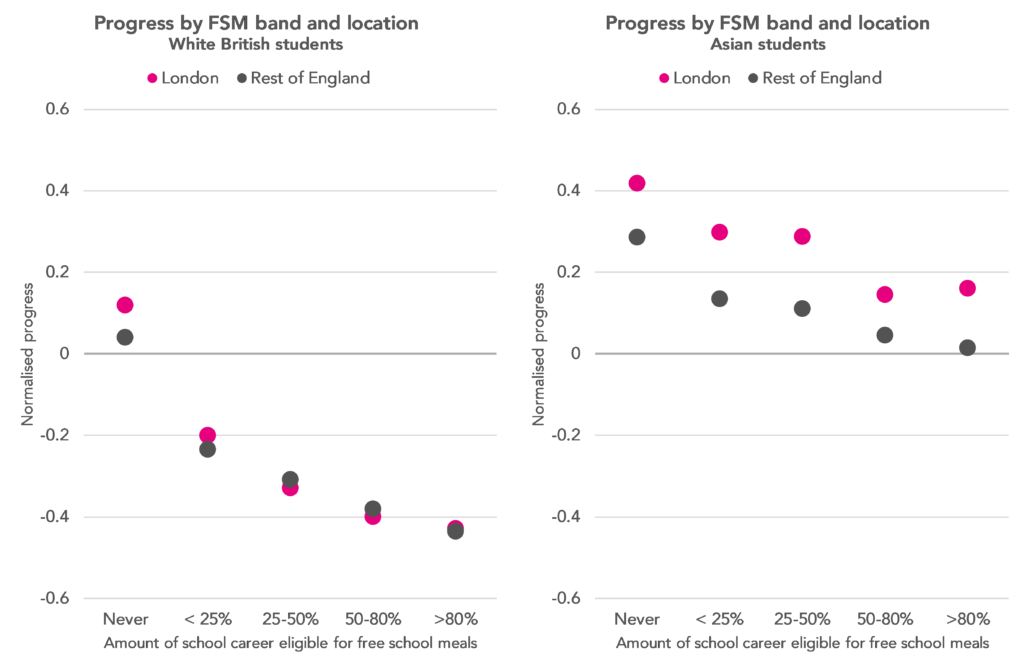

In this paper, he was able to show that white British students performed no better in London than outside. He showed the same for Asian students, and went on to argue that different ethnic groups performed at the same level in London as outside, and the London effect was entirely explained by the ethnic make-up of the capital.

That analysis was carried out on 2013 data. What we’ve seen in the 2018 data backs up Burgess’s findings on white British students, but things look rather different when we consider Asian students.

In the graphs below, students have been split into bands according to the proportion of their school career for which they were eligible for free schools meals. We see a clear difference in performance between Asian students in London and elsewhere, but very little difference for white British students, especially those who are disadvantaged.

So the London effect can’t be entirely explained by the higher proportion of white British students outside London. Although this group of pupils aren’t making any more progress in London than elsewhere, some groups of pupils are.

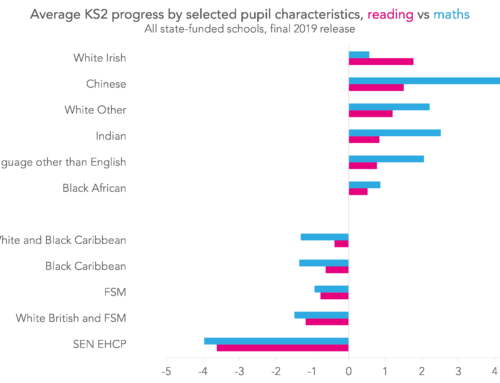

English and maths

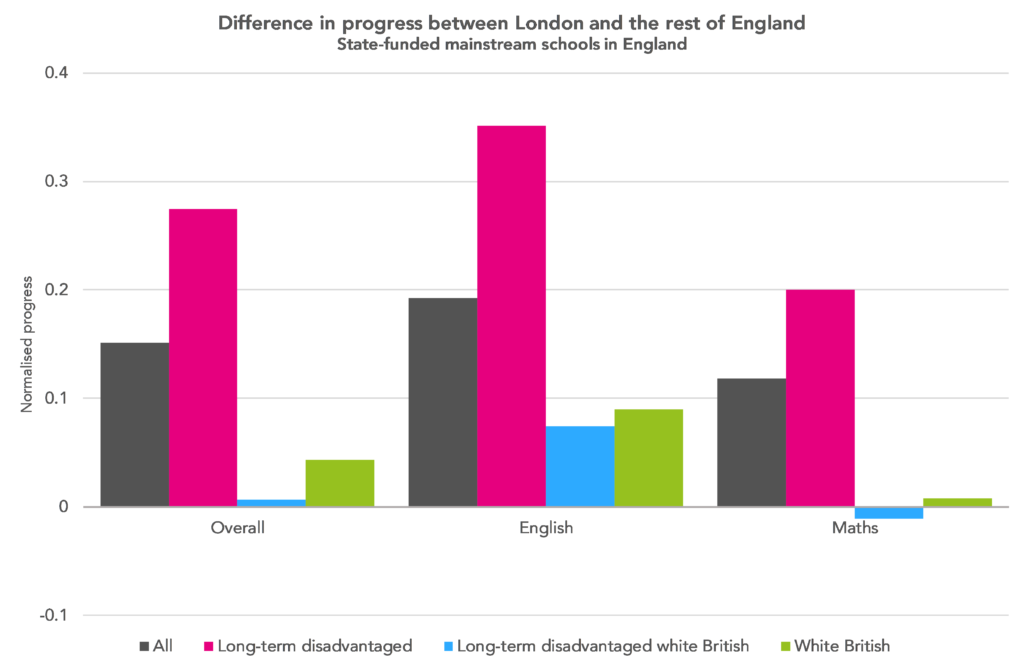

In part one of this series, we looked at how progress in English and maths at GCSE differs between London and the rest of the country, and argued that considering progress in these subjects might give a more reliable indication of the London effect than progress based on overall measures of attainment that combine the results of different qualifications.

We found a particularly strong London effect on English.

But does that hold true for long-term disadvantaged white British students?

The graph below looks at the difference in progress in London and outside, for the same three progress measures considered before. While the difference for long-term disadvantaged white British students is virtually zero overall, and slightly negative for maths, there does seem to be a small effect for English.

Summing up

It still looks as though there may be a little bit more to the London effect than just the basic demographic variables we have used here. Some ethnic groups do better in the capital than elsewhere, and even long-term disadvantaged white British students make (a little bit) more progress in English.

On the other hand, the London effect is negligible for long-term disadvantaged white British pupils when we look at all (or at least the best eight) subjects taken by a student. Although London might be doing something right, its schools have no more effect on this group than schools in other regions.

We also mustn’t ignore the fact that London schools have historically been better funded than those in other parts of the country.

As we wrote some time ago, it seems that some groups of pupils started to make more progress in particular types of school which are more likely to be found in London. We have yet to really crack whether the schools improved the pupils or the pupils improved the schools.

Want to stay up-to-date with the latest research from FFT Education Datalab? Sign up to Datalab’s mailing list to get notifications about new blogposts, or to receive the team’s half-termly newsletter.

Given that Pakistani attainment and progress is significantly lower than Indian attainment and progress and lower than Bangladeshi attainment and progress, should we take a more nuanced view that builds in variation in density of Pakistani populations (higher in Birmingham than London, for example)?

Hi Graham. Thanks for commenting. Yes, I agree. We’ve looked at this in the background but had to leave it out to keep the blogposts brief and comparable with the previous work. Broadly, there is a London advantage for each subgroup within the Asian category but particularly within the Pakistani group (and therefore less so within the Indian and Bangladeshi groups). Of course, the Pakistani group in London may be structurally different to Pakistani pupils elsewhere in the country for reasons we don’t observe in the data. We’ll put out a further update if we can.

One major problem is factors which are not reflected in the school data collected by DfE. Inner London has almost double the proportion of graduates as northern and midlands regions. Recent research by Steve Strand also suggests that primary pupils labeled EAL in some northern local authorities have a lower proficiency in English than in parts of the south. Without some proxy data to reflect these factors, it is difficult to reach conclusive explanations.

When a category like “long-term disadvantaged white British’ is used, we don’t see the realities and experiences behind it, including the chronic demoralisation of many deindustrialised areas in much of the North East, for example.

Thanks for taking time to comment Terry. I certainly agree with the first couple of points. There may well be important differences in family background/ parental occupation driving the differences we see in attainment in London (and Birmingham). As for proficiency in English, DfE started then abandoned data collection. If proficiency was lower in the north this would widen the gap between London and the north. However, I remain intrigued by the fact that White British pupils who experience free school meal eligibility perform no differently in London (or any other region, for that matter). It’s a system-wide issue, one that I doubt could ever be solved by schools alone.