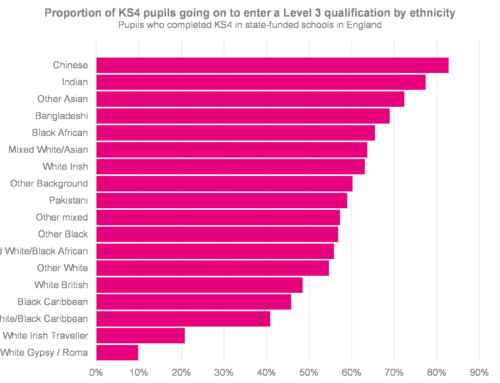

The Minister of State for Schools, Nick Gibb, appeared before the Education Select Committee last week as part of their inquiry into left behind white pupils from disadvantaged background.

He drew attention to differences in rates of entry to the full suite of 5 English Baccalaureate (EBacc) subjects (English, maths, science, humanities and a modern or ancient foreign language) among disadvantaged pupils in different parts of the country.

He contrasted the highest performing local authority on this measure, Newham in London, with three northern local authorities: Blackpool, Hartlepool and Middlesbrough.

Ian Mearns challenged the Minister that these were areas with very different job markets and economic and social conditions. This was dismissed. For the Minister it was about expectations, behaviour policy and curriculum.

But it seems to me that it mostly down to entry in modern foreign languages (MFL).

The puce bars in the chart below show the percentage of pupils entering all five EBacc subjects in the four local authorities. These are the figures quoted by the Minister and show stark differences between Newham and the three northern areas.

Alongside those figures are the percentages of pupils entering all four EBacc subjects other than MFL. On this measure, the differences are much less stark. In other words, disadvantaged pupils in the northern authorities are taking GCSEs in “academic” subjects, just not so much in MFL.

Chicken versus egg

The government set a target that 75% of pupils would enter GCSEs in all five EBacc subjects by 2022 and 90% by 2025.

Even the 75% target was some way off by the end of 2019 as we wrote here. Low take-up of MFL was the main cause.

We’ll leave to one side whether it’s appropriate for 90% of pupils to study all five EBacc subjects.

Why do less than half of pupils in state-funded schools enter MFL each year? Is it because, as Gibb argues, schools have low expectations of some pupils? Or are there structural problems, such as a lack of teachers, preventing them from running more MFL classes?

Back in 2016, before DfE set its 90% target, we estimated that we would need an extra 3,400 MFL teachers to deliver EBacc for all.

By November 2019 [1], according to DfE workforce statistics, the number of MFL teachers in state-funded schools in England has fallen by over 1000 since 2015. By contrast, the number of teachers in history, another EBacc subject with similar(ish) numbers of teachers, has increased by almost 500 (excuse the truncated axis).

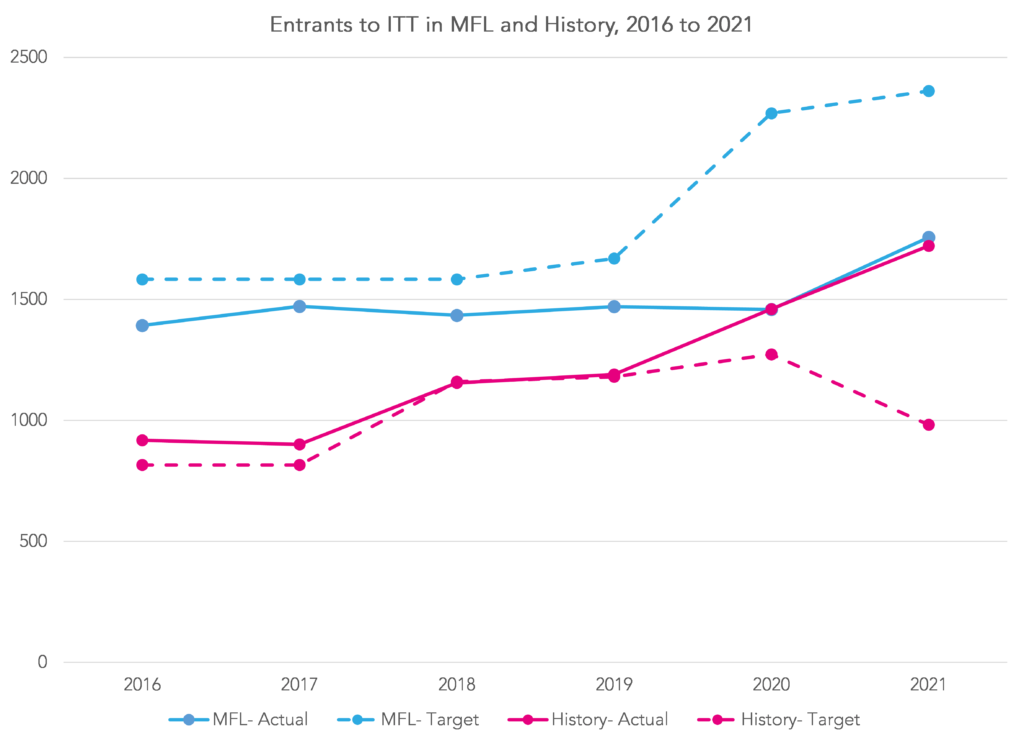

DfE statistics on recruitment to initial teacher training (ITT) show that, between 2016 and 2021, 1400 to 1500 new MFL teachers entered the profession each year. These figures were short of target, especially this year when the target was raised by more than a third. By contrast, there was above-target recruitment in history.

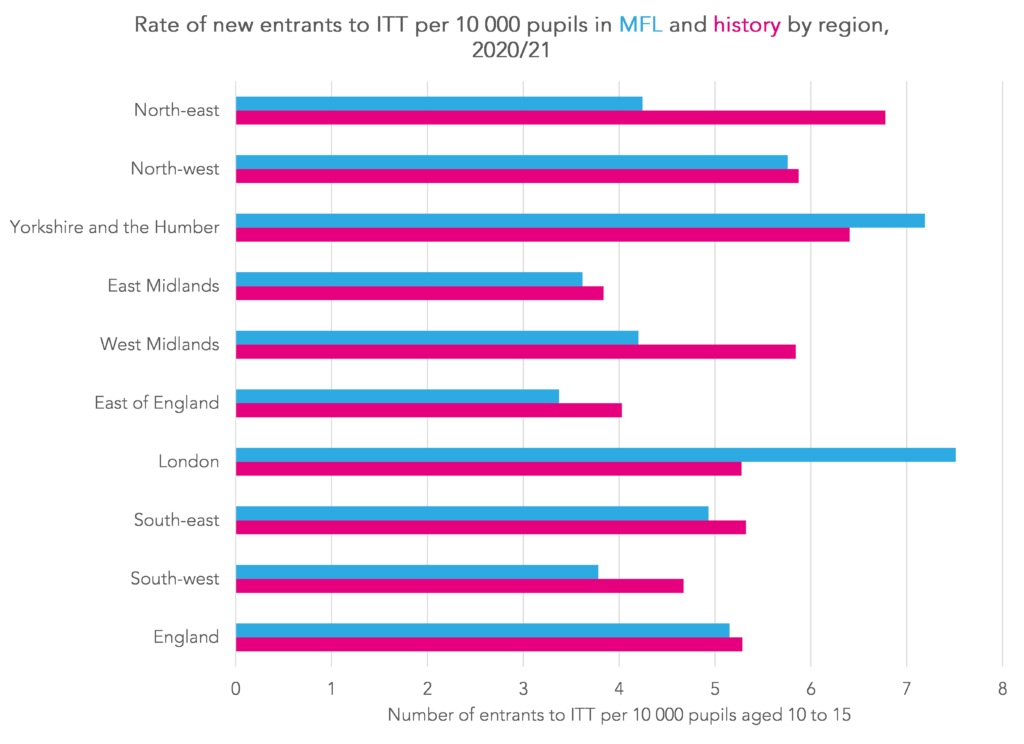

It is noteworthy how regionally concentrated providers of MFL trainees are. In the chart below, we take the published number of trainees at each ITT provider [XLS] and sum to regional level. We then divide by the number of pupils aged 11 to 15 (Years 7 to 11) in schools (including independent schools) to give an approximate rate of trainees per 10 thousand pupils in each region.

The caveat that trainees may not be located in the same region as the registered address of their initial teacher training provider notwithstanding, this chart shows an over-concentration of MFL trainees in London where the rate is more than double than that in the East Midlands and the East of England. In the north-east, there are far more entrants in history than in MFL.

If more MFL teaching takes place in London then perhaps there are more opportunities to place trainees in London’s schools. This wouldn’t be a problem if the trainees were geographically mobile once trained. But if they aren’t, then this would reinforce London’s position as the region with the highest rate of MFL entry (leaving aside the fact that some of London’s advantage stems from entry in community languages).

In passing, it is also worth noting that 30% of the 20/21 cohort of MFL entrants were nationals of the European Economic Area (EEA). Next year’s ITT data may reveal whether Brexit has had any impact on the supply of new MFL teachers.

On top of that, there isn’t space to go into here about whether there are enough MFL graduates to enter teacher training in the first place. Nor discuss whether severity of grading in MFL acts as a disincentive to raising entry rates.

Summing up

If the government wishes to advance the argument that low take-up of MFL is due to low expectations then it firstly needs to assure the sector that a) there are sufficient MFL teachers in the country and b) the labour market is sufficiently mobile to meet demand.

In other words, what assurance can the government give that the supply of MFL teachers can reach the parts the EBacc hasn’t reached?

Want to stay up-to-date with the latest research from FFT Education Datalab? Sign up to Datalab’s mailing list to get notifications about new blogposts, or to receive the team’s half-termly newsletter.

1.Data for the 2020/21 year will be published in the summer.

How important are community languages to the higher rate in London? Can it be quantified in some way?

Hi Edward. Overall in London somewhere in the region of 60% of pupils entered MFL (may have been 2018 last time I looked) and restricting this to French, German and Spanish reduces this by about 5 percentage points.

It’s striking that MFL is the issue. It would be worth exploring the link with numbers of EAL pupils – very few across North East, also in coastal towns such as Blackpool. That affects attitudes to languages, but also many Newham pupils may be taking exams in their family / heritage language as their EBacc language.

Hi Terry. Yes, I looked at White British separately when putting the article together. There were fairly low numbers in Newham (<100 in the 2019 cohort) but they still had much higher rates of entry in MFL.

You may not answer as it’s not specifically about MFL Why are children only allowed to choose either Geography or History for the Ebac and they can’t do both now. What if a child wants to do both if they love both subjects. They may want to do them at A level. So instead they have to take French which they may not want to do. I have been told it is due to the curriculum changes brought in by the government – so there is too much content to cover so pupils can’t do both Geog and Hostory. Is this the same in every school? What about private schools? It seems children aren’t able to choose the subjects they enjoy but only have certain options to study at GCSE

Hello. This sounds like it’s due to the way the school has organised its timetable. There are schools where pupils are able to study both but it’s also common to only have the choice of one. The government wants almost all pupils to take English language, English literature, maths, 2 sciences, geography or history and a language so perhaps the school has organised its options/ timetables accordingly.

Thank you

My experience as a ITT MFL lecturer in one of the institutions (which provided 12 trainees for the year of the data) is that some of them can’t find jobs in the area they want to live. Schools are happy to keep their current number of MFL teachers and therefore restrict the number of pupils taking GCSE MFL. In order to increase take up at GCSE they would have to employ another teacher. It’s a vicious circle. Also, logistically, MFL is pitted on the timetable against subjects like Media Studies or Art which pupils find they are more able to achieve better grades at.

We always have a number of EU nationals training with us and this continues with applications for next year (including also applications from S American countries for Spanish). I can see that trainees will have to come from other countries as UK undergraduate linguists continue to dry up.

Management in schools is also not always enthusiastic about persuading more children to opt to take MFL as they think its perceived difficulty and lower outcomes will affect the school’s overall grades.

Thanks Jean- really helpful comments. What I don’t have much feel for is how many MFL teachers there are out there who want to work teaching it in school (and where they are located). And as you say, there may well be other factors affecting schools’ decisions to offer MFL even if there were an adequate supply. Good to hear that overseas nationals are still filling the breach.

As already noted, MFL entry is skewed significantly by EAL, especially when a home language is studied. Newham does have very high %EAL students – especially in their highest performing schools. It would be very interesting to see what Ebacc figures/MFL outcomes would be like if EAL entries were removed from the stats. It would not offer a more balanced view necessarily, as context is key. It would just offer an interesting perspective.

Hi Steven. Yes, in fact I had initially planned to do something along those lines but there are so few disadvantaged non-EAL students in Newham I decided to include just the stats for all disadvantaged young people.

Thank you.