Last week the Mayor of London announced funding to extend universal free school meals to pupils in Years 3 to 6 in all state-funded schools in the capital in 2023/24. Some local authorities[1] already run their own local schemes.

The announcement has been broadly welcomed but some concerns have been raised about whether the amount of funding is sufficient and whether there may be a fall in parents claiming free school meal eligibility which, in turn, would have an effect on schools’ pupil premium funding.

You might think there are good moral arguments for universal free school meal provision. Alternatively you might think better use could be made of the money.

We only do data so we’re not going to get into that here.

Instead, we’re going to have a think about how the impact of extending free school meal eligibility on absence and attainment might be measured.

Measuring impact

Researchers from the Institute for Social and Economic Research (ISER) at the University of Essex have previously evaluated the impact of universal free school meals for infants (Reception to Year 2). They found small but positive impacts on absence, obesity and household expenditure.

Extending free school meal eligibility in the capital gives us a rare opportunity to measure the impact of extending universal free school meals to older pupils, even if that isn’t necessarily an aim of the policy.

The problem in assessing impact is that the scheme is running in just one region, London, and that region is very different to the rest of the country. For example, published DfE statistics show that almost half of pupils in primary schools in London have a first language other than English (national average of 21%).

In an ideal evaluation, the scheme would have been rolled out in half of schools in London, with schools selected by lottery. This would have given us a conventional “treatment” and “control” group. But this probably would have been seen as unfair by those attending schools that missed out.

So instead, we’ll have to make best use of observational data to try and estimate what would have happened in London in 2023/24 had universal free school meal eligibility not been extended. This would be compared with what actually happened to give us an estimate of the impact of the policy.

There are more or less complicated ways of arriving at this estimate. I’m going to illustrate some simple methods that show the basic problems researchers will have to overcome.

Absence

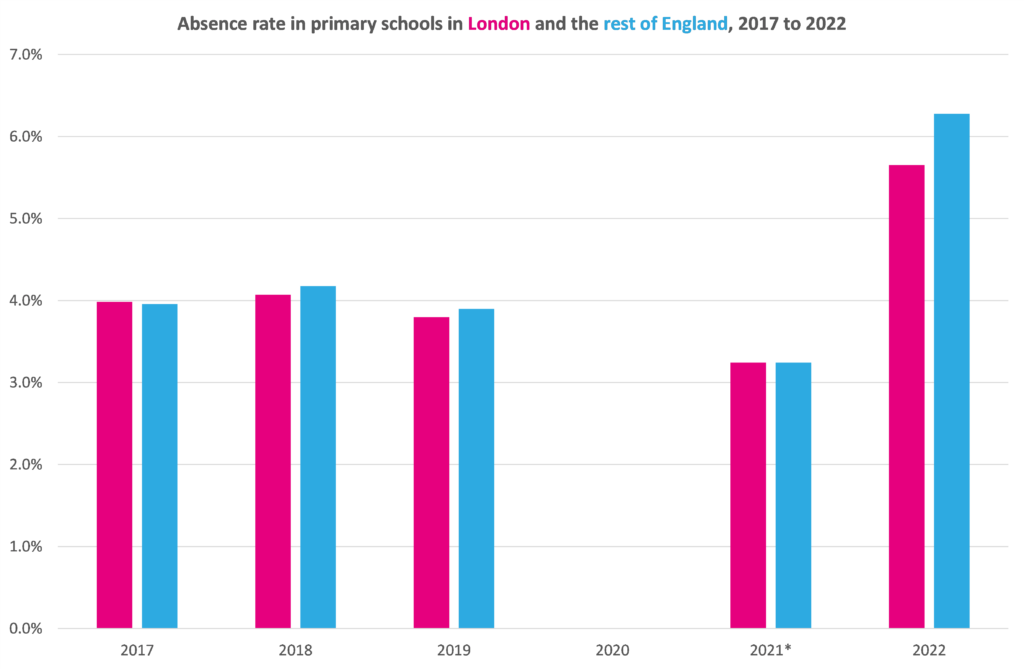

For the purposes of this illustration, I’m going to use published DfE statistics of absence in primary schools in the Autumn and Spring terms.

In an ideal world, I’d have used data for the whole academic year but the full year dataset for 2021/22 had not been published at the time of writing. I would also ideally restrict the analysis to Years 3 to 6 as they are the cohorts affected by the policy.

Firstly, I compare absence in London schools with the national average. I don’t include the four local authorities which already provide universal free school meals[1] in the London average.

For the three years prior to the pandemic, there was very little difference in absence between London and the rest of England. No data is available for 2020. In 2021, there was again little difference [2]. But in 2022 absence was lower in London than the rest of the country.

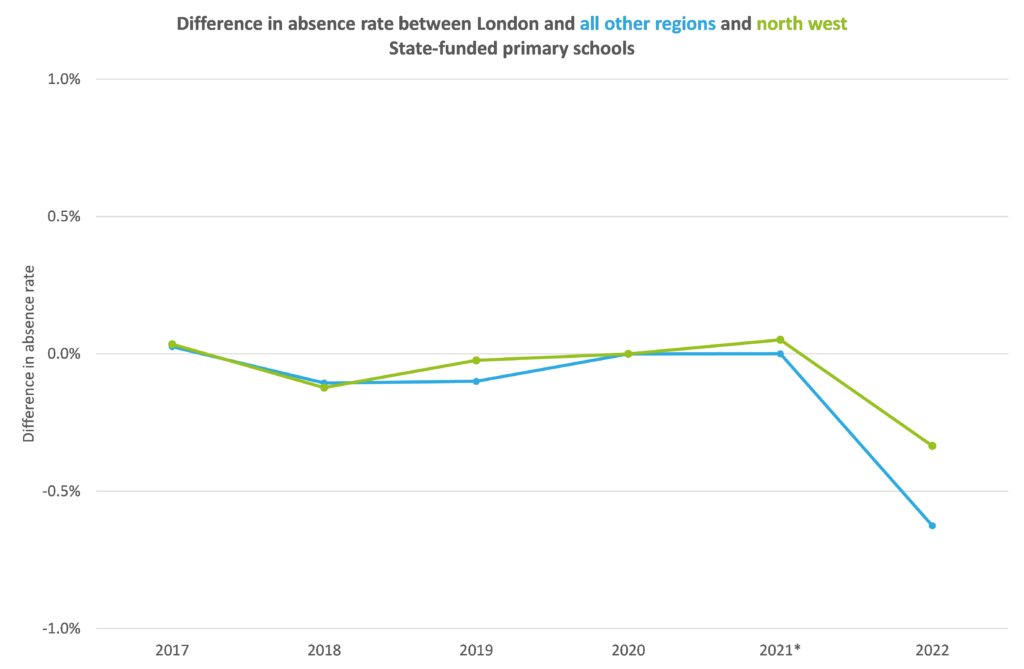

Over this period, absence in London’s schools has been more similar to that in schools in the North West than the rest of England as a whole.

In the next chart we show the difference in absence rates between primary schools in London and a) all other regions in England and b) just the North West. These differences need to be considered in the context of the size of the impact on absence of universal free school meals for infants detected by ISER of around 0.6 pp.

Absences in London in 2022 were 0.3 percentage points (pp) lower than in the North West. This is a smaller figure than if we compared London to all other regions (0.6 pp lower). So in the absence of any policies targeted at London in the 2022/23 academic year, we might expect absence in primary schools in London to remain similar to that in the North West.

However, early data for this year suggests that absence in London is unexpectedly 0.7pp higher than the North West.

So when researchers come to evaluate the impact of extending universal free school meals in London on absence, they will have to deal with volatility in absence data in recent years. Any results that indicate an effect of the policy may be attributable to other reasons, including local patterns of illness.

Attainment

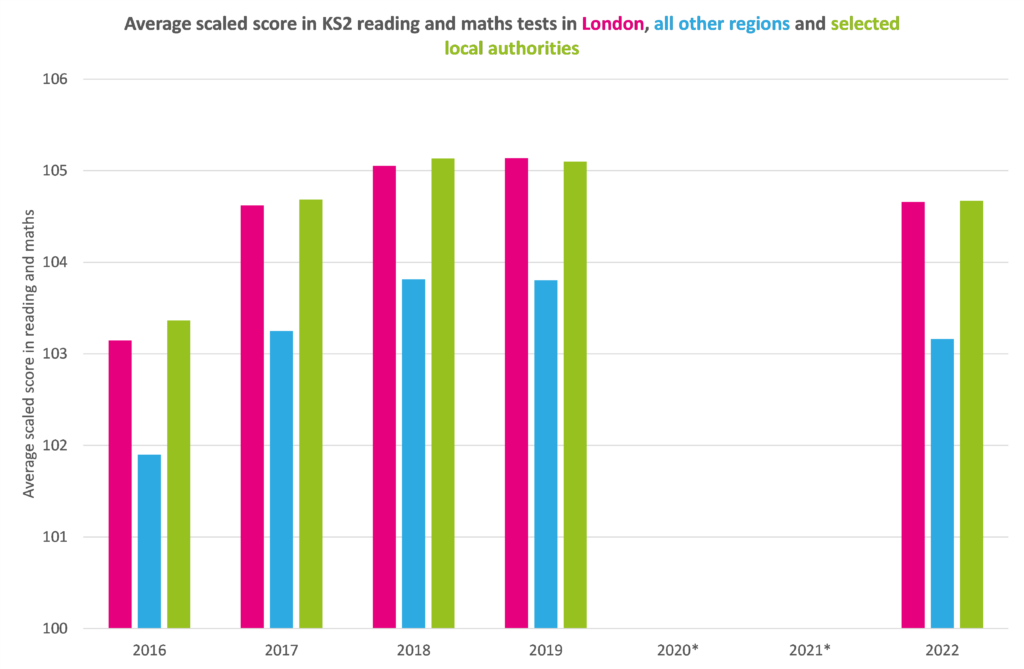

Key Stage 2 tests returned in 2022 after a two year hiatus. As was the case before the pandemic, London was the highest-attaining region.

For this illustration, we use the average scaled score in Key Stage 2 reading and maths tests. Scaled scores range from 80 to 120 with 100 denoting an expected standard. DfE report the average scaled scores in 2022 to have been 105 in reading and 104 in maths.

However, these national averages do not include pupils who do not enter the tests because they are considered to be working at a lower level. We assign a notional score of 75 to these pupils and recalculate the average scaled score in reading and maths for each local authority and for each region.

The average scaled score achieved in London in 2022 was 1.5 points higher than in other regions. This was slightly higher than the differences pre-pandemic.

Also in the chart we show a comparison between London and “selected local authorities”[3]. These could make a good comparator for London as differences have tended to be fairly minimal (0.01 in 2022, for example).

Other, more complex, variations of this approach exist in which local authorities are weighted (based on historic performance and perhaps other data) to create a comparison group. One example we particularly like is the covariate balancing propensity score. But the basic principle is the same.

Summing up

The extension of universal free school meal eligibility to pupils in Years 3-6 that will take place in London in 2023/24 will represent a rare opportunity to evaluate its impact on attainment and absence.

This is important because claims are often made about the benefits of universal free school meals which make assumptions about the size of these effects.

An example is the cost benefit analysis produced by Price Waterhouse Coopers for Impact on Urban Health. This calculated that universal free school meals would more than pay for itself in the long run.

Their calculations included a sequence of assumptions which went like this:

- Implementing universal FSM will lead to a 5 percentage point decrease in absence

- This in turn will lead to a 16 percentage point increase in individuals achieving 5 or more GCSEs at grades A*-C (9-4 in new money) including English and maths

- These individuals will earn an extra £127,000 in their lifetime than they would have done otherwise.

The very first assumption seems rather large given the ISER study, in which they found that universal infant free school meals led to a decrease in absence of just 0.6 percentage points.

The second assumption assumes a causal relationship between absence and attainment. Although the two are certainly correlated (pupils with lower absence tend to be higher attaining), common underlying factors (such as disadvantage) may be driving both to a greater or lesser extent.

A good evaluation of the London policy could therefore produce good evidence of the impact on attainment and absence, albeit for primary-age pupils. It would also only cover the short-term (one year) impact. But this will nonetheless be very valuable in understanding the costs and benefits of universal free school meals.

- Islington, Newham, Southwark, Tower Hamlets

- Note that absence statistics for 2021 exclude sessions missed for reasons connected with Covid-19, such as isolation

- Buckinghamshire, Hertfordshire, Rutland, Slough, Surrey, Trafford, Warrington, Windsor and Maidenhead, Wokingham, York

Want to stay up-to-date with the latest research from FFT Education Datalab? Sign up to Datalab’s mailing list to get notifications about new blogposts, or to receive the team’s half-termly newsletter.

Readers might be interested to know that ISER are following up their study of universal infant FSM, with another study funded by the Nuffield Foundation. This is investigating the longer-term impacts of free school meal provision on attainment, bodyweight and absences up to age 11, through analysis of earlier and different ongoing local authority free school meal programmes: https://www.nuffieldfoundation.org/project/the-impacts-of-universal-free-school-meal-schemes-in-england.