In this blogpost we’re going to tackle a difficult question [1]: whether having an EHC plan can prevent exclusion and repeat suspension.

The challenge in answering it is one of what economists call selection. The factors that lead to some pupils having EHC plans and others not may be related to the propensity to be excluded. If EHC plans were handed out at random, as they would be in a randomized controlled trial, for example, this would not be a problem. But an RCT of EHC plans is never going to happen.

So what we have to do is try our best with existing data. We do this using an approach known as Instrumental Variables (IV).

This involves finding another variable which increases the probability of receiving an EHC plan but should not otherwise affect the outcome of interest, in this case exclusion.

The variable we use for this is month of birth.

Data

We use data from National Pupil Database (NPD) and analyse a single cohort: pupils in Year 7 in the January School Census of 2017.

This provides us with some basic information about pupils, including whether or not they have an EHC plan, their month of birth, ethnic background and gender.

We add further data known to be correlated with exclusion and suspension during secondary school (see here for example), namely disadvantage (percentage of terms eligible for free school meals up to Year 7), history of involvement with Children’s Social Care (ever in need or ever in care) and number of previous suspensions/ exclusions at primary school.

We observe exclusions from Year 7 in 2017 to Year 11 in 2021. We recognise that this is a period affected by Covid-19 and hence exclusions would have been lower than if the pandemic had not occurred.

We also calculate a measure of repeat suspension from Year 7 to Year 11. This is defined as 3 or more suspensions over that period.

Basic statistics

First of all, let’s take a look at exclusion and repeat suspension rates broken down by Year 7 SEN status.

We see that pupils with EHC plans were less likely than pupils with SEN met by SEN support to be excluded or experience repeat suspension.

They were also marginally less likely than pupils not identified as having SEN to be excluded although more likely to experience repeat suspension.

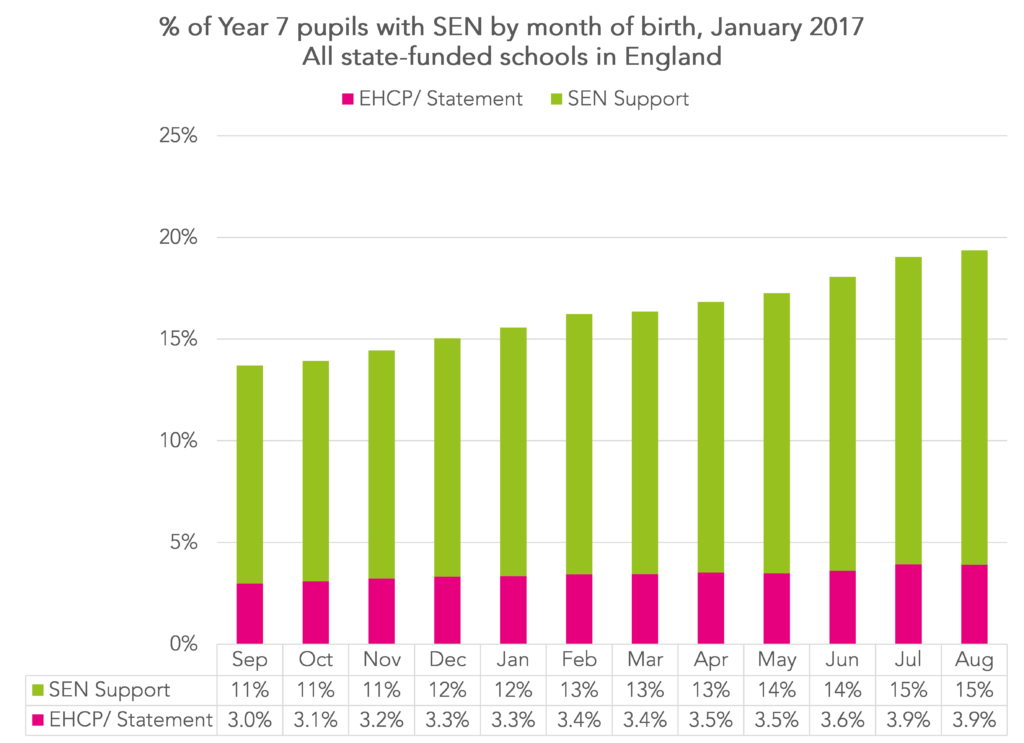

Now let’s turn to our proposed instrumental variable: month of birth and whether it increases the probability of having an EHC plan.

On the surface, this seems to be the case. 3.0% of September-born pupils had an EHC plan compared to 3.9% of August-born pupils.

Instrumental Variables

For a good primer on the logic of the instrumental variables method, read the relevant chapter in this handbook on causal inference.

In brief, it is a 2-stage least squares regression. In stage 1, we calculate the probability of having an EHC plan given a pupil’s month of birth (and other relevant variables). In stage 2, this probability is used (also along with other relevant variables) to calculate the probability of being excluded (or experiencing repeat suspension).

The coefficient associated with the probability provides an estimate of the effect of the impact of having an EHC plan on the outcome.

We run two specifications: 1) a basic specification in which the only other factor is gender and 2) additionally including % of terms eligible for free school meals, IDACI score of home postcode, ethnic background and whether (or not) previously in need or in care.

We also run what is known as a “naïve specification”, a single stage ordinary least squares (OLS) regression in which the variable relating to having an EHC plan is included (instead of the probability used in the 2 stage regression). However, the results from this have a different interpretation to the IV results[2].

We also run the models on the subset of pupils who had experienced suspension at primary school.

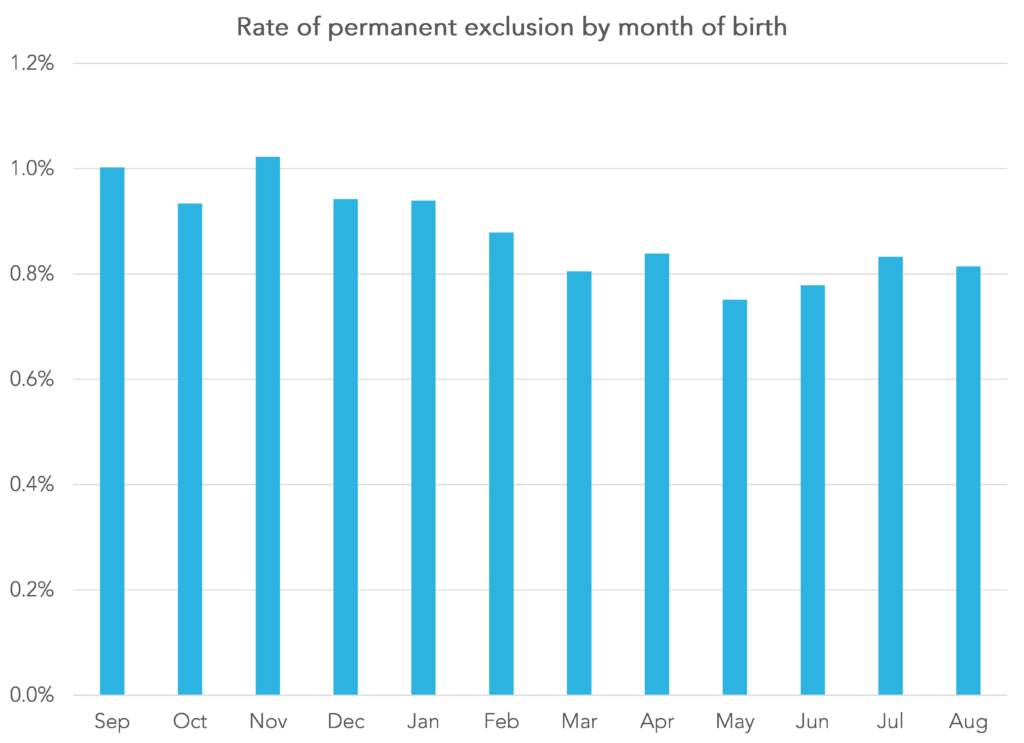

The results are only as good as the untestable assumption that we make: that exclusion (or suspension) is unrelated to month of birth. We couldn’t use this method to analyse the impact of EHC plans on attainment, for example, as we know that summer born pupils tend to be lower attaining.

Among pupils in the cohort we use here, we see that pupils born in the Autumn were slightly more likely to be excluded.

Is this driven purely by SEN identification? Or could there be other factors at play? Do let us know any thoughts in the comments.

Results

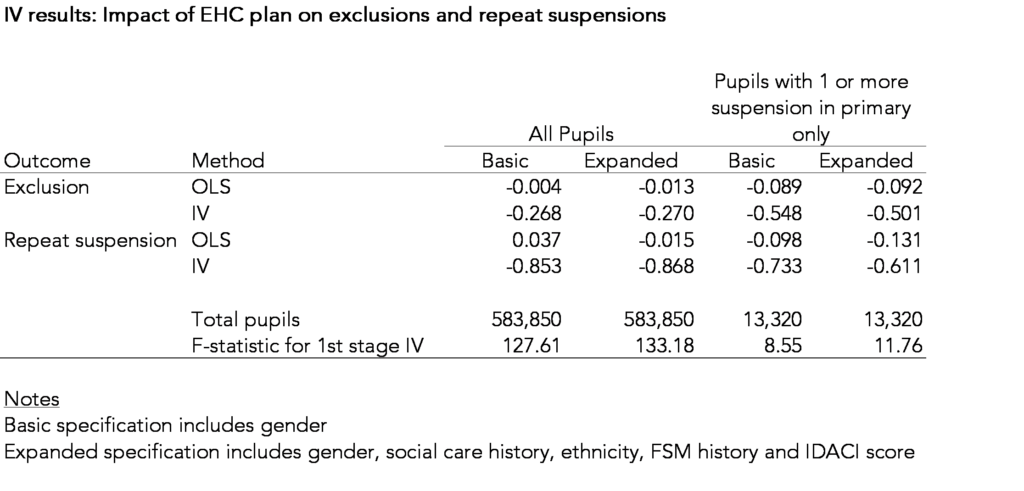

We present results for both outcomes (exclusions and repeat suspensions) using both the OLS and IV (2 stage least squares) methods. We do this a) including all pupils and b) just for the subset of pupils who experienced exclusion or suspension during primary school.

Under OLS (ignoring completely the non-random allocation of EHC plans), pupils with EHC plans tend to have a fractionally lower probability of being excluded. However, this increases substantially in size under the IV method. Results for the basic and expanded specifications are broadly similar.

For repeat suspensions, pupils with EHC plans have a slightly higher probability than other pupils under the basic OLS specification. This flips sign (i.e. they have a slightly lower probability than other pupils) when the expanded specification is used. However, the IV method shows a substantially lower probability compared to other pupils.

On the surface then, this would tend to suggest that EHC plans may play a part in preventing exclusion and repeat suspension.

Summing up

In this article we’ve tried to examine whether EHC plans prevent exclusions and repeat suspensions using an instrumental variables technique, exploiting the fact that summer born pupils tend to be more likely than autumn born pupils to be allocated EHC plans.

On the surface, it suggests that EHC plans are preventative.

This raises two questions.

Firstly, whether month of birth is a valid instrument. To answer this, we need to probe more fully the relationship between month of birth and exclusion (or repeat suspensions). Apart from increasing the likelihood of having an EHC plan, is there any other reason why summer born pupils would be less likely to be excluded (or experience repeat suspensions)?

Secondly, if we cannot think of anything, does it suggest that more pupils might benefit from an EHC plan? Or are there procedures for pupils with EHC plans at risk of exclusion that could be made more widely available?

Understanding the costs of issuing more EHC plans in relation to the lifetime costs of exclusion would be helpful. Some estimates of the latter would be a useful starting point in this regard.

Thanks to Richard Dorsett for comments on this article.

- Although we’re going to stop short of actually answering it.

- The naïve specification estimates the effect of receiving an EHC plan for pupils who receive one on the assumption of random selection. The IV specification estimates the effect of the an EHC plan of the group who received one but would not have done had they been born earlier in the year.

Want to stay up-to-date with the latest research from FFT Education Datalab? Sign up to Datalab’s mailing list to get notifications about new blogposts, or to receive the team’s half-termly newsletter.

There are reasons other than EHCPs that might explain the pattern of exclusions. Perhaps those who are excluded are bigger and stronger and, therefore, more dominant and less likely to conform to how their peers behave.

As for the IV approach, did you look at the pattern of exclusions by month of birth for pupils without EHCPs? If it shows the same pattern, then wouldn’t that rule out the possibility that EHCPs make the difference?

Thanks Andrew. Yes, your first point could well be plausible and would thus invalidate the IV approach. On the 2nd point, yes I did look at this. IIRC it was pretty similar to the chart in the article (based on all pupils). I favoured this version as it was unaffected by the selection issue, i.e. the variation in EHCP allocation by month of birth.

Doesn’t that rule out the possibility of the EHCP being the mechanism by which the month of birth affects exclusions? If it was, you’d expect the pattern for non-EHCP pupils to be without that correlation (although it might be distorted in other ways by the selection).

Yes, if there’s something else causing the remaining imbalance in rates by month of birth then I need to control for it, if I can. Which first means working out what it is.

Wild speculation, because why not… “is there any other reason why summer born pupils would be less likely to be excluded?”

1) on average they are smaller – so less likely to start fights/intimidate teachers etc?

2) being younger, less likely to drink/smoke do other age restricted activities?